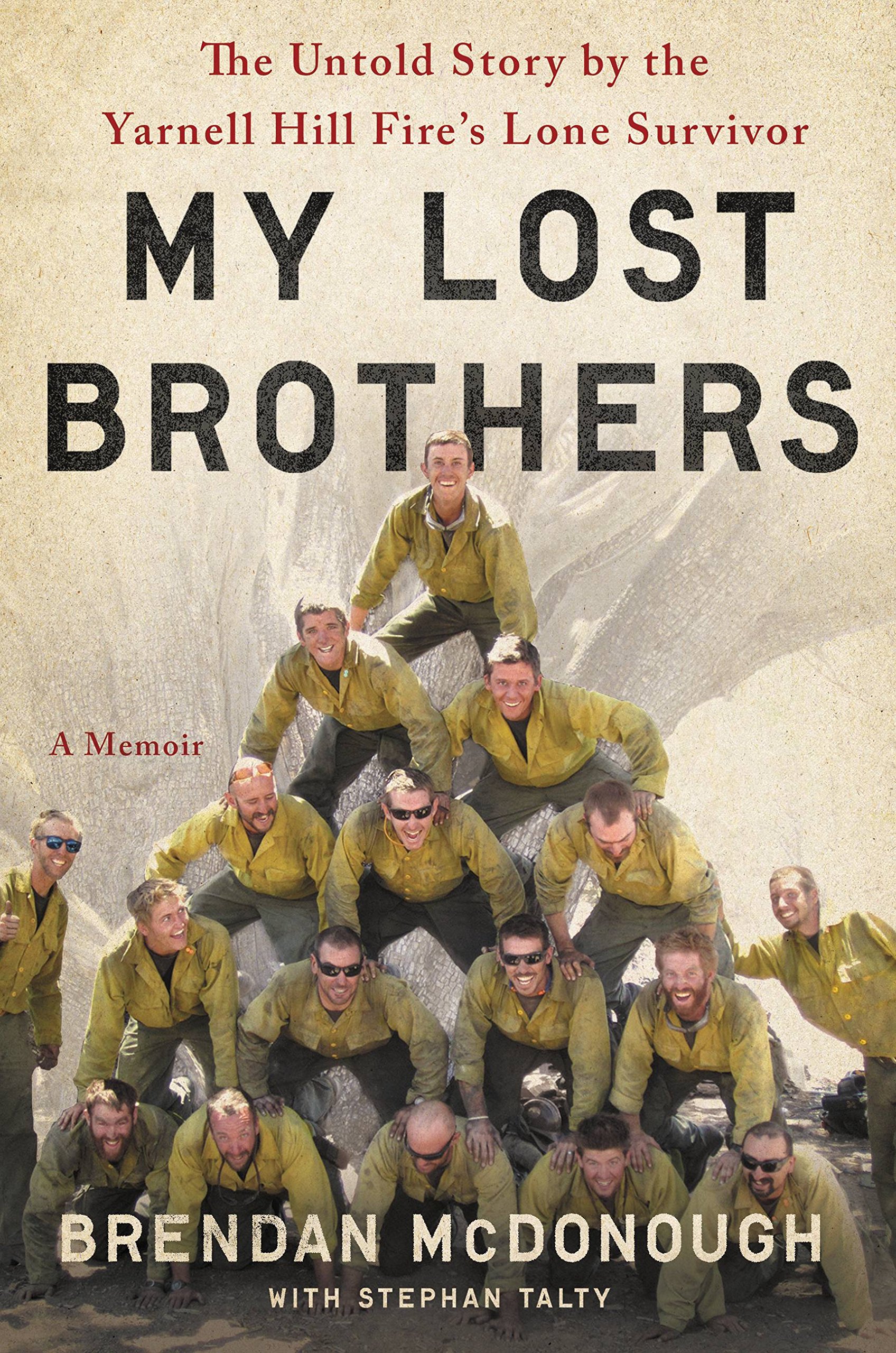

Brendan McDonough is the author of My Lost Brothers.

Nineteen firefighters from the Granite Mountain Hotshots lost their lives in the 2013 wildfire in Yarnell, Ariz. Brendan McDonough is the crew’s sole survivor. Below he describes a fire they fought 12 days before, and how he honors their memories.

We all knew the names of wildfires that hadn’t ended well: the Great Hinckley Fire in Minnesota, the 1990 Dude Fire, the Oakland Firestorm, Mann Gulch. Each one had different causes, different conditions, different terrains. But they all shared one factor: tinderbox dryness in the brush and wood that fueled them. And that sure as hell was true for Prescott, Ariz., where I was stationed as part of the Granite Mountain crew of wildland firefighters. It was drought conditions here—and we’d just spotted smoke.

It went to black against the dome of blue sky. Then it started moving to the northeast, faster. The radio crackled. “Crew Seven.”

That was us. We started the buggies, big white Ford F-450 trucks with equipment lockers above our heads that held our packs, bins on the side of the trucks that held all our other gear, and captain’s chairs for us to sit on during the drive to the fire line. The drivers revved the engines and tore out of the station’s driveway.

The guys were amped. You could feel it. It reminded me of those soldiers at Stalingrad: The fire was threatening our homes, our families. It was time to fight.

My crew mate Chris and I found a gap in the brush, and he went first. We began burning, one eye on the flames and one on the ground ahead of us. We were carving a burned-out barrier to stop the flames before they reached town.

The fire was moving so damn fast. It was 200 yards away now and the noise was building. A mountain-sized lion roaring, that’s what it sounded like. Burning embers flew through the air, lighting up spot fires ahead of the fire wall.

I began to hear a particular sound. The sound of a freight train.

An out-of-control wildfire that is bearing down on you makes a sound like a freight train, or really a hundred freight trains shooting out steam at high pressure. Not only that, but each burst of sound seems to spawn three more, until there’s this infinitely expanding roar ripping in your ears.

Hotshots believe that once you hear that sound, you’re nearly out of time. If the wildfire caught Chris and me, we’d either be dead or suffer 100% body burns. There were no other options. We ran.

Chris was shouting, but now his voice was sucked in by the howling of the fire. Our brothers were somewhere through the wall of brush, but no one could hear us.

I saw daylight ahead and the dark flat shape of asphalt. With one last grunt, Chris jerked me free of the brush. The air was clean and not too hot. We sucked it in greedily. I felt pure animal joy surging through my gut. We got out of that alive.

That was 12 days before Yarnell and the fire that killed 19 of my brothers, while I was serving as a lookout in a different location.

Wildfires are getting bigger. They’re burning hotter, wider, and longer. Thousands of firefighters are in the field in the West—and it’s not enough. The government is giving National Guard troops emergency wildfire training so they can help out crews that are stretched beyond their limits.

I’m the first to admit I’m not an expert. I was a seasonal employee who saw a lot of action during a time of drought. But three seasons was enough to at least show that there was a problem in how we fight wildfires nationally. The system we have isn’t working, period. We need innovation in how we fight wildfires. The hard-working men and women who fight fires need to come home at night to the people who love them.

I go to the Pioneers’ Home Cemetery in Prescott to visit the graves of my brothers when I can. Not too often, to be honest. It’s painful, still, more than I can describe.

But I love this place, in a way. I’ve told my family I want to be buried here. That was an easy call. I want to be with my brothers. That’s where home has been for me ever since I met them. There’s no point in remembering me without remembering Eric and Jesse and Chris and Travis and the rest of the boys, because without them I would have been a different man, a far less honorable person.

Is it strange, at 23-years-old, to think about my burial plot? Not for me. It’s the continuation of what I feel now. I think about the guys every day; I talk to them. There’s not a day goes by that I don’t encounter a situation where a lesson one of the Granite Mountain guys taught me comes to mind. It could be how to treat every moment with my daughter, Michaela, like it could be my last.

Do I always live up to their memories? Hell no. I mess up all the time. But I never even had that ideal to try to reach before. Now I do. Those guys are with me as much as my daughter or my mother is, and so I look forward to being alongside them for good.

Therapy has gotten me here, talking through that day at Yarnell and untangling the emotions that come with it. I’ll never lose the horrible memories I have, but I can change the way I feel about them.

The memorials, the faces, the crinkly feel of those orange body bags, they’re part of me. But I’ve been allowed to grieve these men now. I’ve accepted that I couldn’t have saved them, no matter what I did.

What happened was a wildfire that ran out of control. I didn’t fail my brothers, and they didn’t abandon me.

Only by learning to live with what happened at Yarnell, and accepting the gift that my brothers gave me, can I be with the people I love.

Adapted from My Lost Brothers: The Untold Story by the Yarnell Hill Fire’s Lone Survivor, copyright © 2016 by Brendan McDonough. First hardcover edition published May 3, 2016, by Hachette Books. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com