Donald Trump has some of the most valuable golf courses in the world—just ask him.

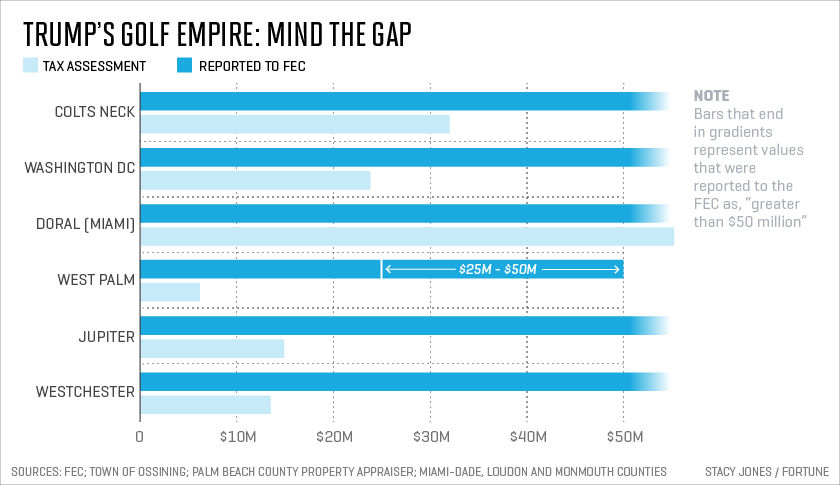

In July, as part of his bid for the Republican presidential nomination, Trump declared that seven of his 12 domestic courses were worth at least $50 million each. One course, the Trump’s West Palm Beach, he even counted twice, saying it was worth over $50 million for the course and the same for the fact that members of Mar-a-Lago Club pay for access to it—for a total of $100 million when it came to measuring his net worth.

But when local governments try to tax Trump on his golf properties, he incredulously turns out his pockets, often claiming that his courses are worth far less than the estimates on his nomination filings. Trump and his subsidiaries have employed this tactic with at least six of his U.S. courses, according to town and county officials in numerous states. In at least one instance, the discrepancy between what Trump said a course would sell for when claiming to the public he’s worth “TEN BILLION DOLLARS” and what he told local officials come tax time was at least $48.6 million, or 97% less.

Why Trump is fighting these valuations seems clear: He’s trying to save money on his tax bill. No one with knowledge of the situation is claiming Trump is breaking the law. The real estate developer, like others, appears to be exploiting a tax loophole that is pretty common in municipal law, having to do with something called current use.

At issue is how local governments tend to do their assessments. Most municipalities will appraise real estate for tax purposes based on how much the property is generating in income as is, and not on what the land could generate if it were to sell to a developer looking to turn a golf course into a residential development or a condo community. In other words, the intrinsic value of the property may far exceed the tax assessment because municipalities do their calculations based on the current use.

Fighting the assessed values is something Trump has done for years, and he’s far from the only developer who does it. Trump doesn’t try to hide his tax maneuvers or feel it needs to be justified any more than anyone would justify paying more for a better tax accountant. “I want to reduce the taxes, and I feel it’s overvalued as a golf course,” Trump explains.

But in the past 10 months, as Trump has made his bid for president he has used the opposite tactic in tallying up what he is worth, often going with the much higher values the golf courses could go for in sales. Why he would list the values of these courses well above their current use also appears obvious: to make his assets seem maximally valuable.

Asked how he reconciles valuing his golf properties at one amount in his candidacy filings and then claiming they’re actually worth a fraction of those figures for tax purposes, Trump said it’s a matter of the properties’ potential values.

“As a development site, they’re unbelievably valuable,” Trump says. “I could convert Doral [in Miami] into thousands and thousands of [housing] units, but that is a different value as golf. It was always very important to me to have the land. I always want to have the option. ”

How Trump handles the valuations on his golf properties—inflating their theoretical value to boost the perception of his wealth while simultaneously claiming local tax assessors are overvaluing the same courses—is just another window into how he’s run his campaign, as well as his casinos and other business over the years, as Fortune detailed here: Business the Trump Way. It is another sign, Trump supporters would say, of the GOP nominee’s shrewd business sense.

But in municipalities across the country that have tangled with Trump, the tactic has been seen as a means to put his own interests way in front of the communities he does business in. What’s more, while other developers seek to lower their tax bills, experts say the vast ocean of difference between Trump’s public disclosure of the properties’ worth vs. what he says the value is when seeking relief on local taxes—and how hard he fights for that relief—seems to be considerably larger than is typical in real estate circles.

“That’s what happens when property owners who have the money and the ability to hire lawyers, and can grieve their taxes, are successful,” says Dana Levenberg, a town supervisor, and Democrat, in Ossining, N.Y. “Everyone else has to pick up the difference … In this case, we are not the powerful. This is local government, vs. a real estate tycoon … So how do we get ahead?”

Mike Raio, an assessor in Pine Hill, N.J.—home to Trump’s eponymous Philadelphia course, which Trump valued at between $5 million and $25 million on his financial filing for his presidential run—confirms that Trump’s golf properties are taxed only as golf courses and would be more valuable as housing lots. The same case can be made at any of the other locations of Trump’s courses, because of their vast acreage and prime locations.

“An area like ours [around Philadelphia], in today’s market, you’d put down apartment units. Something that big, you could probably get a few hundred units on there. At $150,000 a unit, $100,000 a unit, you’d have a much more valuable property, Raio explains.

But this isn’t the whole story. The conversion from open space recreation use to housing is a lengthy process. One cannot simply assume the conversion of a property from one to the other, Vince McClaren, a commercial appraiser in the West Palm Beach property appraiser’s office says.

“Until someone comes in and applies for a zoning change, or a use change, or approval, and that’s approved, I can’t make that assumption [with the assessment].”

That approval process is lengthy and rigorous, particularly in counties who may already have a highly saturated housing market. There are certainly no guarantees of a successful transition.

In short, Trump’s explanation makes sense in theory, but in practice it’s much more complicated.

But for municipalities big and small, from Ossining to Miami-Dade County, the cost of Trump’s tax challenges is not esoteric or theoretical. It’s very real, and potentially very expensive.

Take Trump National-Westchester in the suburbs northeast of New York City, which Trump valued on his candidacy filings at more than $50 million. According to the Town of Ossining, the property is taxed at a much lower valuation of $14.3 million, and yet Trump is still fighting the town, insisting his course is worth a mere $1.4 million.

If Trump gets his way, the developer would only have to pay Ossining a mere $47,000 in property taxes, according to The Journal News, down from the $471,000 the town would like to charge him, which is still far below the $1.7 million Trump would have to pay a year if the property were valued same as it was on his own net worth statement. The biggest loser could be Ossining’s school district, which will be left with $255,000 less if Trump wins his fight with the town. Not to mention the costs to the city for defending the valuation. A property expert alone cost the town $25,000 at the last hearing, according to assessor Fernando Gonzalez.

That means tens of thousands of dollars in lost tax revenue, plus thousands of dollars in costs even if the town ends up being right.

And Trump has had some success in winning these tax fights. At Trump Doral in Miami, site of the WGC-Cadillac Championship, Trump won a reduction is his property’s assessed value of just shy of $8.8 million for 2014, resulting in nearly $150,000 in tax savings according to a Miami-Dade County records. That’s money the county literally had to refund Trump. He’s currently contesting his 2015 valuation as well, which the county assessed at $55 million, even though the officials believe the property to worth nearly $70 million.

Only a recent law declaring a cap on tax increases on property prevents the county from levying the full amount. In other words, he’s fighting the valuation of a property that is already being taxed at well below what the county believes to be its true market value. Even that might be low. Trump bought the Doral course for $104 million.

Palm Beach County records show that Trump has pending tax disputes at all three of his Florida courses: Trump National West Palm Beach, Trump National Jupiter, whose assessed value Trump has contested three years running, as well as the tax fight over Doral.

Trump lost his Jupiter appeal for 2015 at a hearing in February where he asked for a reduction from $14.4 million to between $4 and 5 million in 2015. The county lists the market value at $17.1 million.

At Trump West Palm Beach, where the county lists the market value at $7.63 million, Trump is taxed at just under $6.2 million because the county actually owns the land and the course leases it.

Trump’s dispute at that property was withdrawn the day before a hearing was supposed to be held Feb. 18th. No specific value for reduction was requested.

But even in a case where a local municipality wins, it still has to go through a lengthy process. The Palm Beach County property appraiser’s office spends nearly half the year tied up in disputes, but Vince McClaren says only about 10%-to-15% of the over 120 golf courses in the county file these disputes, adding it’s usually the same ones every year.

It costs just $15 to file a petition by the petitioner, but ties up staff for weeks at a time, and costs the county to hold hearings in front of magistrates.

This sets up a Trump Rorschach test: his supporters will say he’s a private citizen fighting the tentacles of government that unfairly reaches into the pockets of the wealthy. His critics will say this is shady math the real estate mogul uses to oversell his wealth when it suits him but talks a very different tune when faced with the burden of taxes.

The local fallout from Trump’s tactics with his golf properties may not matter for the average businessman, but the average businessman isn’t running for president.

This article originally appeared on Fortune.com

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com