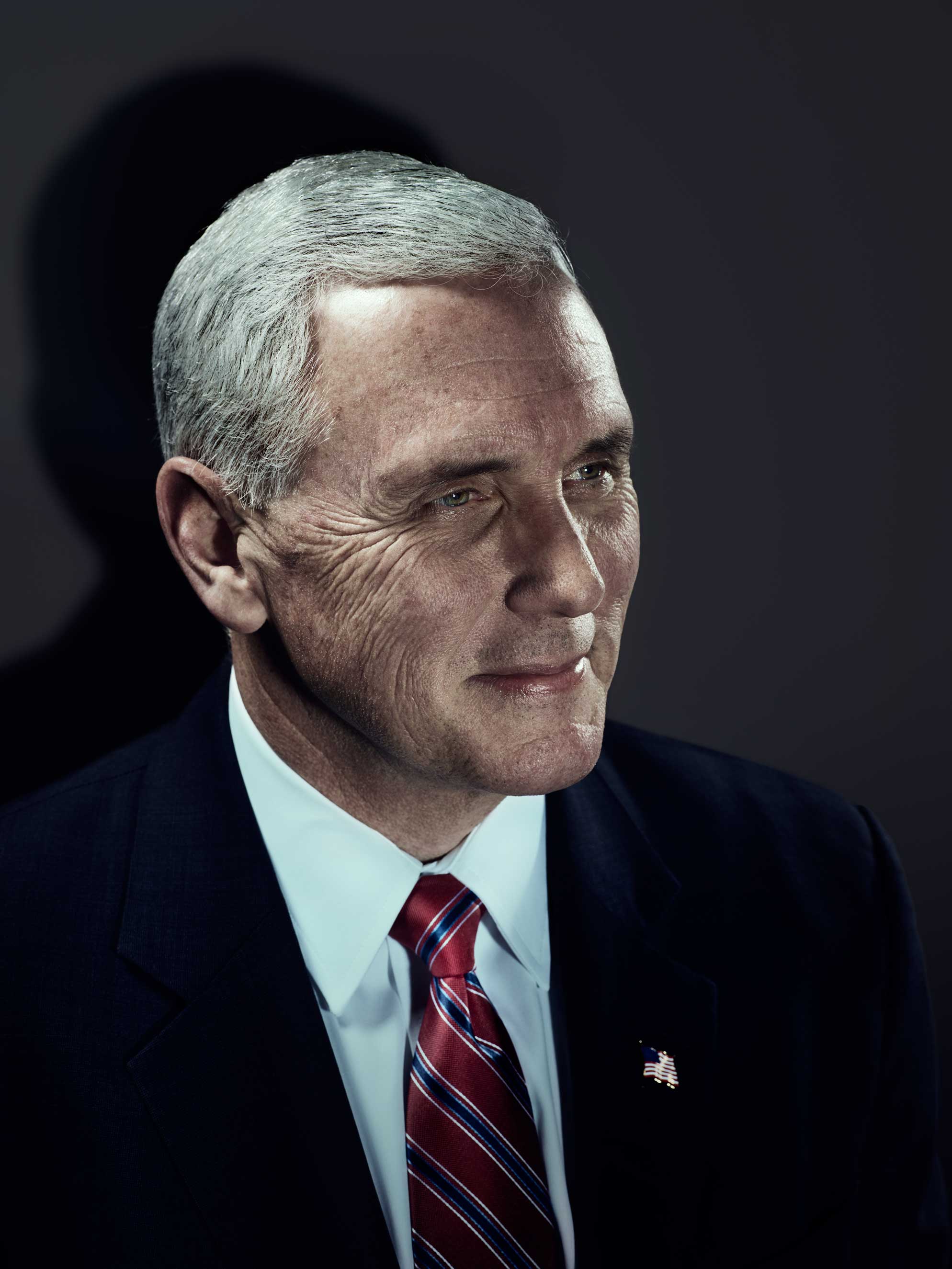

House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi kept her fingers interlocked on the polished table, a smile fixed to her face. This was not how she had hoped to spend the weeks after the 2016 election, sitting next to Vice President–elect Mike Pence. But the voters had called the shot. If there was any consolation to the awkward scene, it was that the two power brokers had known each other for years, well enough that when Pelosi dropped protocol to call him “Mike,” he laughed and welcomed the informality. “You’re going to be a very valuable player in all of this,” she said to Pence, “because you know the territory, and I know–with no disrespect for the sensitivity and knowledge of the President-elect–you know the territory. So in that territory, we will try to find our common ground where we can.”

It’s a good bet that Pelosi intended to throw some shade on President-elect Donald Trump. But Pence let it blow by because he knew what he was there to do. There is no one in America, save the President-elect himself, who has more responsibility to make Trump’s first term a success. Key among Pence’s tasks, after staffing the new Administration and keeping the peace with conservative activists, is finding a way to reach across party lines to make the government work. Perhaps that’s why he described his meeting with Pelosi as the first of many, called her “a worthy opponent” and reflected fondly on their debates over the years in the House. That same day, he offered incoming Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer his personal cell-phone number with an open invitation to call. “Politics is the art of the possible, and knowing people and having relationships is finding out what is possible,” Pence told TIME weeks later during a brief interview at Trump Tower.

After 12 years in Washington as a Congressman (before becoming governor of Indiana), Pence has been putting a lot of his relationships to work. “If the President-elect is wise enough to use him very extensively, I think he will serve himself very well,” former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels tells TIME. “So much of what Vice President Pence brings fills gaps in President Trump’s background.”

Pence has already made a mark. “One of my great decisions in life was choosing Mike Pence to be my running mate,” Trump tells TIME. “He is truly a high-quality human being, first class in every respect. He is also a talented politician who loves people and wants to help them every step of the way.”

Pence installed allies to head the CIA and the Department of Health and Human Services and the Medicare and Medicaid systems. He elevated a fellow Republican governor to become the envoy to the United Nations and another to run the Energy Department. He camped out on cable TV to make the incoming Administration’s case. His goal, as the right hand to a man he once opposed–and still disagrees with on tactics and tone–is to become invaluable. “I don’t think Donald knew him very well,” former House Speaker John Boehner says of Trump’s running mate. “But he has found out over these last four months that he made a much better decision than he realized.”

Little on Pence’s résumé suggests he was destined for his current role. The small-government conservative who fought George W. Bush on a prescription-drug bill now finds himself defending decisions like the Carrier jobs deal, which Tea Party stalwarts call “cronyism and corporate welfare.” The devout evangelical who routinely describes himself as “a Christian, a conservative and a Republican, in that order” helped America elect someone who, before he started running for the White House, might have failed all three tests. A party leader who tried to pass a comprehensive immigration bill that was decried at the time as amnesty stood next to a rabble-rouser who won the White House on the promises of deporting immigrants and building a wall along the Mexican border.

But then, this isn’t the first time Michael Richard Pence, 57, who grew up in a middle-class Democratic house where his family displayed pictures of John F. Kennedy, has surprised. His path has never followed a straight line. He arrived on Indiana’s Hanover College campus in 1977 as a fairly typical young person: somewhat liberal, open-minded and curious about what lay beyond his experiences at the St. Columba parish in Columbus, Ind., where he spent at least six days a week as an altar boy. His family didn’t talk politics at home, but Pence had an interest. He collected a box full of news clippings about JFK, and at age 15 he was a volunteer for the Bartholomew County Democrats. “Dad didn’t like politicians or lawyers,” he told the Indianapolis Business Journal in 1994. Pence would become both.

Despite his Catholic heritage, he gravitated toward the evangelical groups on campus–because they were more fun and seemed to have a more personal relationship with Jesus, he says. “I gave my life to Jesus Christ, and that’s changed everything,” Pence said in 2010. Even as he came to describe himself as an evangelical, he continued to attend Mass, where he met his future wife Karen, with whom he would have three children. At the same time, Pence was growing uncomfortable with his Democratic Party’s support for abortion rights. (He still voted for Jimmy Carter over Ronald Reagan in 1980.)

After college, he considered graduate school and even the priesthood. Instead he settled on law school and spent four years as a corporate attorney. Yet the political bug kept nipping at him, and in 1988, at age 29, he decided to challenge Democratic incumbent Phil Sharp in the state’s then Second Congressional District. Pence launched a scrappy first campaign, riding his single-speed bicycle across the district, but the thing Hoosiers remember more than his glad-handing is his stomach for negative ads. One flyer featured a picture of rolled-up cash, razor blades and white powder that looked like cocaine. There’s something Phil Sharp isn’t telling you about his record on drugs, it read. On the next page, spelled out in fauxcaine: it’s weak.

Pence lost by more than 6 percentage points. He tried again two years later, with another viciously negative strategy. In one Pence ad, a man dressed in Arab garb thanked Sharp for keeping the U.S. reliant on Mideast oil. Pence supporters posed as members of an environmental group and called neighbors to tell them, incorrectly, that Sharp was turning his family farm into a nuclear-waste dump. Pence, who claimed not to know about the scheme, would later recognize the calls as “a manifestly dumb idea.”

In the end, only 42% of voters backed him, and Pence went home a deeply disappointed man with a guilty conscience. As penance, he wrote Sharp an apology letter and later published a manifesto against negative campaigns. “Christ Jesus came to save sinners, among whom I am foremost of all,” Pence wrote, quoting Scripture. These “Confessions of a Negative Campaigner” became a guiding principle for his future campaigns, still a decade away, and the next step of his career as a conservative policy thinker and talk-radio host. In an era of red-meat radio, Pence cast himself as a calmer alternative, “Rush Limbaugh on decaf,” he said. The remake worked, allowing him to finally win the House seat in 2000.

Pence arrived in Washington a year later determined to rise through the ranks, but not by playing along. He was one of 34 Republicans who voted against the Bush education overhaul branded No Child Left Behind, which increased federal control over grade school, and in 2003 he was one of 25 Republicans who voted against a Medicare program for seniors’ drugs, which added to the deficit. Both, he said, smacked of Big Government. Outside the halls of Congress, he joined a lawsuit seeking to overturn the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance law. John McCain, Pence said in one contentious meeting, was “so deep in bed with the Democrats on this issue that his feet are coming out of the bottom of the sheets.”

Leaders at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue noted his independent streak and uncanny ability to attract press. Those close to Pence attribute his early success to a strong moral compass. After all, Pence kept a Bible within arm’s reach in his office and often cited Scripture to explain his votes. As public opinion was shifting on same-sex marriage, Pence did not waver. “For Mike, it’s more about the right thing to do than the expedient thing to do,” said John Hostettler, a former Congressman from Indiana.

In 2006, Pence tried to midwife an immigration bill that would have offered a path to citizenship for immigrants in the country illegally. The plan won applause from Bush, who invited him to the White House to give his effort some juice. Conservatives called it a betrayal, and the bill never got off the ground.

Even so, Pence caught the eye of party bigwigs. Boehner, then the Republican leader, gave him minor tasks to test both his competence and his loyalty. Pence passed, and in late 2008, Boehner phoned Pence and urged him to throw his name into the race for the No. 3 spot in the GOP leadership, chairman of the House Republican conference. “Really?” came Pence’s reply. “Can I call you back?”

Boehner says Pence called him back an hour later and said he would do it. “It was one of the best decisions I made,” Boehner says. “Pence and his team were constant sources of support and good counsel.”

That’s not to say Pence had curbed his independence. Rather, when he disagreed with Boehner, he did so quietly so as not to embarrass his friend, who was struggling to hold together a Republican Party being tugged in competing directions by Bush-style conservatism and the rising Tea Party. It’s a fight that no one has yet won, and one Pence will now try to referee among the shrinking GOP establishment, Trump’s country-club plutocrats and Rust Belt populists who want what they were promised. It may be Pence’s toughest assignment.

Pence’s fans started talking him up as Indiana’s next governor, if not President. He genuinely enjoyed working as Boehner’s eyes and ears among conservatives but also was looking at his next moves. “You can’t have your heart in two places,” Boehner told him.

So Pence returned home to Indiana, knowing that Republicans like to nominate governors over legislators as presidential nominees. Pence went to all corners of the state. This time, it was a Big Red Truck Tour instead of a single-speed bike. He ditched the lawyer’s pinstripes for a leather bomber jacket. He kept his social conservatism in check, preferring to stick to his talking points that promised to take his state “from reform to results.” His campaign had tinges of Make America Great Again.

Pence and Trump first got to know each other on the back nine of the billionaire’s club in Bedminster, N.J., over the Fourth of July holiday, when Trump’s odds of becoming President seemed more certain than Pence’s of winning a second term. In his time as governor of Indiana, he had stumbled, declining in approval ratings and struggling with missteps. “In Washington, where he cut his political teeth, they talk in big ideas. In the states, you have to have results. There’s no place to hide,” says Indiana senate president David Long, a fellow Republican who considers Pence a pal.

Pence had proposed a state-run news agency that drew ire from all corners, not just for its perceived affront to free press but also because of its price tag. He clashed with the Republican-led legislature on the budget and was forced to scale back his cherished cuts in corporate and personal income taxes. Most damaging, he signed a law that supporters said defended their religious freedoms by allowing them to deny services to gays, lesbians and those who are transgender or bisexual. The vocal critics called it discrimination. “Indiana is a state of crisis,” the Indianapolis Star’s editors wrote in a rare Page One editorial. Pence caved, provoking outrage from Christian conservatives who thought he had gone wobbly.

But as the two men approached the 17th hole, Trump wanted to talk about himself and his campaign. He asked Pence how this campaign might end. Pence had no hesitation, he recounted in an interview. “You’re going to be President of the United States,” Pence said.

“Well, that’s pretty definitive,” Trump said in reply. The businessman started seeing the appeal in Pence’s pedigree as a Washington insider, social crusader and state leader. Pence’s stock rose further when he told an NBC News journalist that Trump had “beat me like a drum” on the course.

A few weeks later, Trump came knocking. Literally. His plane just happened to break down in Indianapolis, and the Pences invited Trump and his three eldest children to breakfast at their home the next day. Pence, who in public can be rather stilted, delivered an impassioned indictment of both Bill and Hillary Clinton that was reminiscent of his days as a talk-radio host. By the evening, Trump was signaling that he was inclined to go with Pence, campaign aides told reporters.

Pence’s selection for the ticket proved to be an antidote for the summer’s #NeverTrump fever. Republicans, especially those with Establishment footing, had gnashed their teeth over their nominee for months, fearing Trump was unelectable or, even worse, uncontrollable. But with the mild-mannered Pence at the table, it was acceptable. Trump also dispatched Pence during the campaign to begin to lay the groundwork for an Administration, which the Trump team had always avoided. “We spent exactly zero days in Washington,” Trump’s first campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, says these days. Pence would play catch-up.

Back at the Capitol, GOP Senators made a request to Pence: come to lunch every Tuesday. Republicans in the upper chamber usually hashed out strategy and policy over meals just off the Senate floor every week. Of course he’d be there, he told them during the summer.

Across the Capitol, Pence’s task was to mend fences. A pal of Paul Ryan’s, Pence successfully negotiated the détente between the feuding House Speaker and party nominee. Like a Sunday-school teacher, Pence told the pair to knock it off and get back to the same hymnal. Then after the election, when conservatives threatened Ryan’s role as Speaker, Pence was on the phone calling potential naysayers to tell them that Trump wanted to keep Ryan in that role. And when the full House Republican conference welcomed him back to the panel he once chaired on Nov. 17, he received an extended standing ovation. Pence returned the favor with a strong selfie game, raising an iPhone up a selfie stick. The resulting snapshot was mocked for featuring so many white men. It wasn’t just good manners or efficient photography. It was a down payment to the partners who could help the Trump-Pence Administration. “Buckle up,” he told his former colleagues.

Pence in action over the past few months has been a man who has advanced from Trump’s outer orbit to the center of his inner circle. He defends Trump’s tweet storms, excuses his false statements and backs hires like chief strategist Steve Bannon, who once published blistering criticism of Pence on the website Breitbart. Pence stayed silent when Trump contradicted him during debates and at rallies, and maintained that the President-elect was behind a deal that saved 700 jobs at one Indiana factory. Without Indiana’s economic-development dollars, which Pence still controls, the deal would have been DOA. Loyalty is the ultimate qualification inside Trump Tower, and Pence was rich in that commodity.

In recent weeks, Pence has been the central figure inside Trump’s Administration-in-waiting, interviewing candidates for roles large and small. So much of actually running the government happens in assistant secretaries’ offices, not in the showy spectacles. Pence understands this and is comfortable keeping his hand on the rudder in these offstage moments. For instance, he doled out his cell-phone number to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s board of directors at a recent meeting in Washington. In private, Pence can mellow his billionaire boss.

The question will be, to borrow a phrase Hillary Clinton once said of herself, just how high a pain threshold Pence possesses. His political future hinges on Trump’s fortunes, and his identity could be determined by the policy positions Trump takes. Pence simply cannot run for President in four or eight years if the Trump Administration is a failure. To have a chance at the top job, Pence has to make Trump a winner. And for Pence to maintain his political identity, he has to keep Trump on a conservative path.

But Pence is ultimately a man of faith. As he said in a 2012 farewell speech to the House, things don’t just happen by chance. “When you see a turtle on a fence post,” he said, “one thing you know for sure is that he didn’t get there on his own.” It will be up to Trump how to treat his new tortoise, the slow and steady plodder who might prove a winner in the end. And for now, Mike Pence is fine with that.

This appears in the December 26, 2016 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com