The movie SuperFly that comes out this week shares a name with the 1972 film Super Fly, though “they serve different audiences, they serve different worlds,” as TIME’s film critic Stephanie Zacharek puts it in her review. But, even with all those differences, both movies also share a link to an important part of American history — and the history of LIFE Magazine.

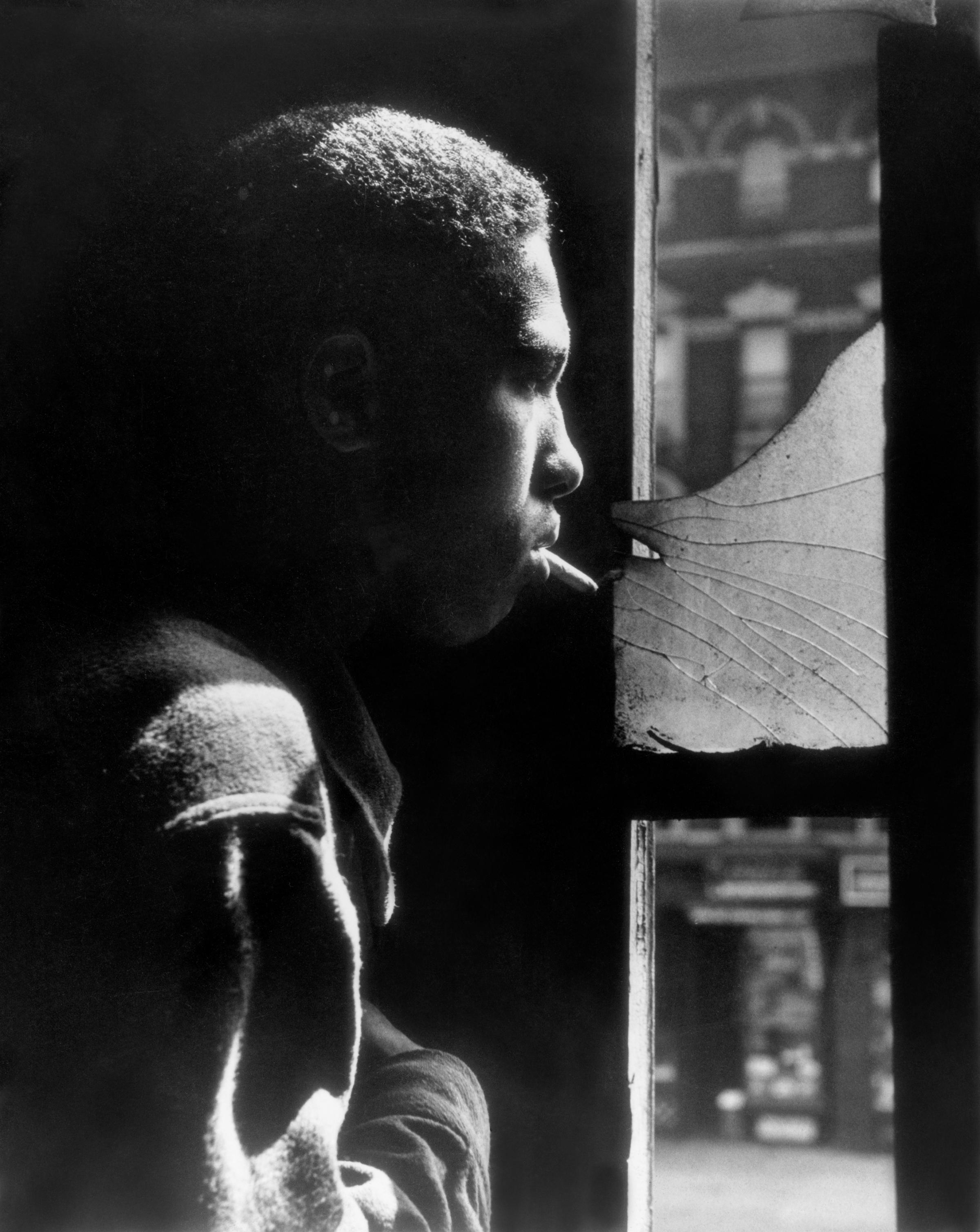

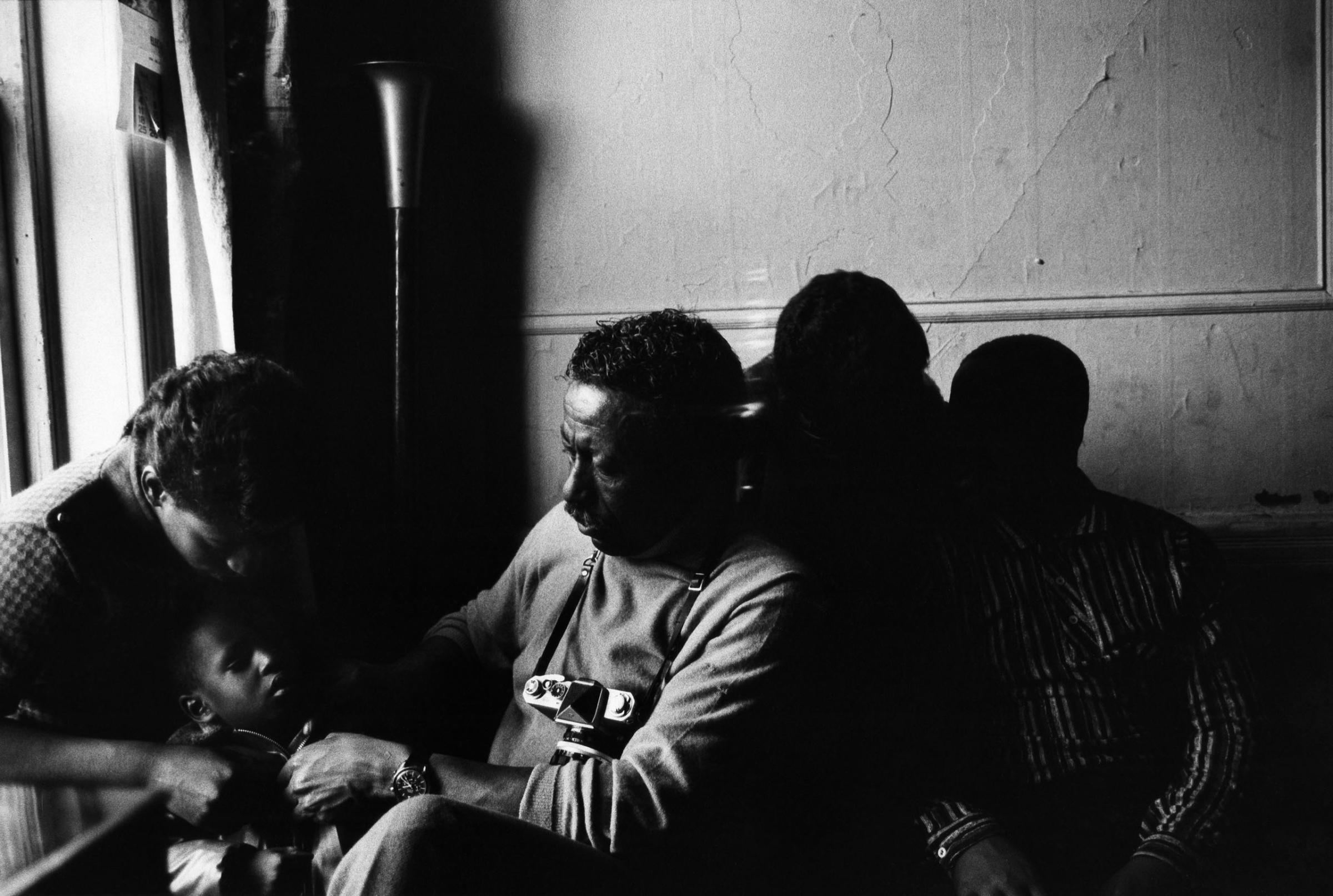

The original Super Fly was directed by Gordon Parks Jr., whose father Gordon Parks, who died at 93 in 2006, was the first African-American staff photographer at LIFE and a co-founder of Essence magazine.

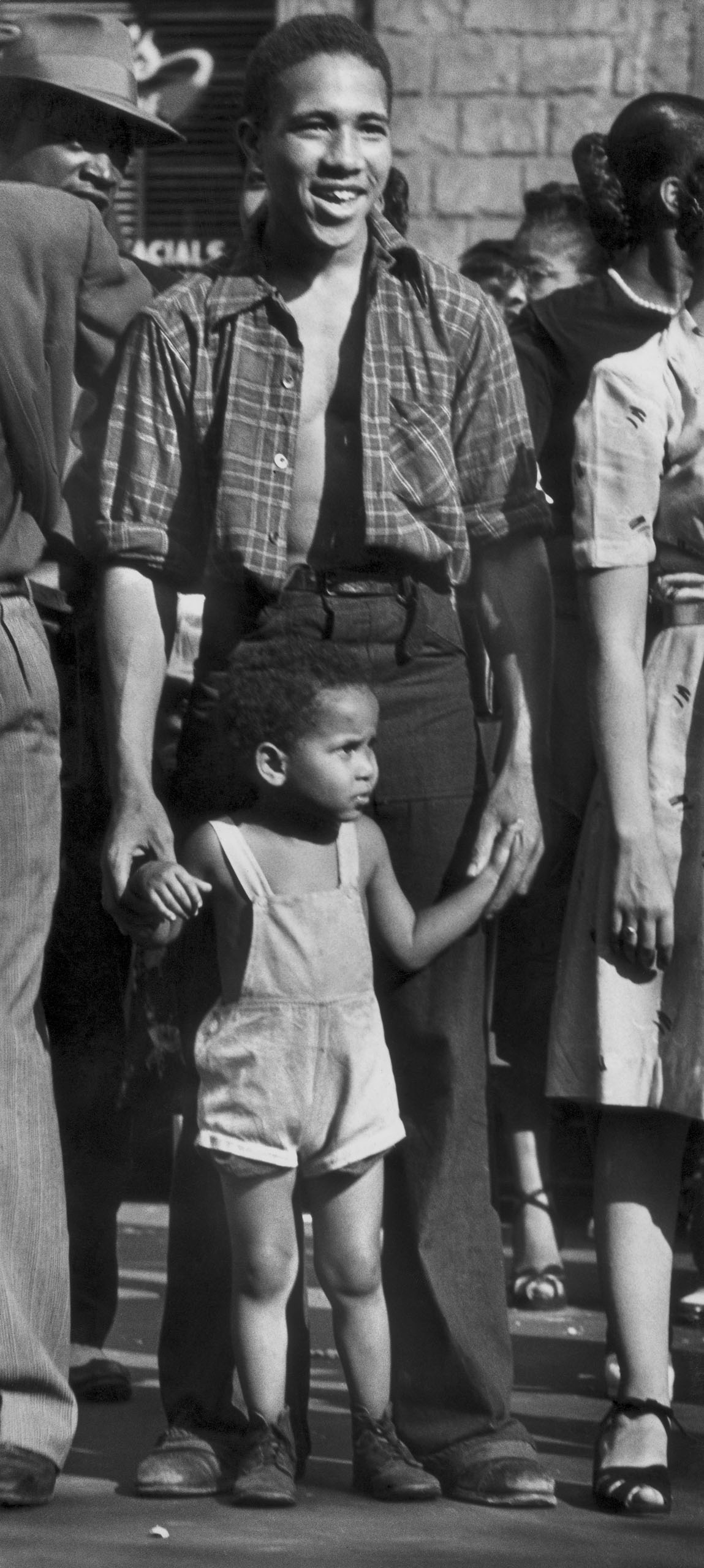

In the autobiographical novel that inspired 1969’s movie The Learning Tree — which made him the first African-American director of a major Hollywood movie — Parks Sr. summed up why he became a photographer. He wrote that he sought to portray “how certain blacks, who were fed up with racism, rebelled against it.” After joining LIFE in 1949, in between photographing subjects as varied as the Paris fashion scene and Benedictine monks, he worked to convince African-Americans readers that they could trust the magazine to tell their stories, even though most of its staffers were white. At the same time, by default, he served as a translator of black life for many of LIFE’s non-African-American readers.

“There is this pressure to make good for your whole people,” he told TIME in 1953. “If you fail, they give you a black eye.”

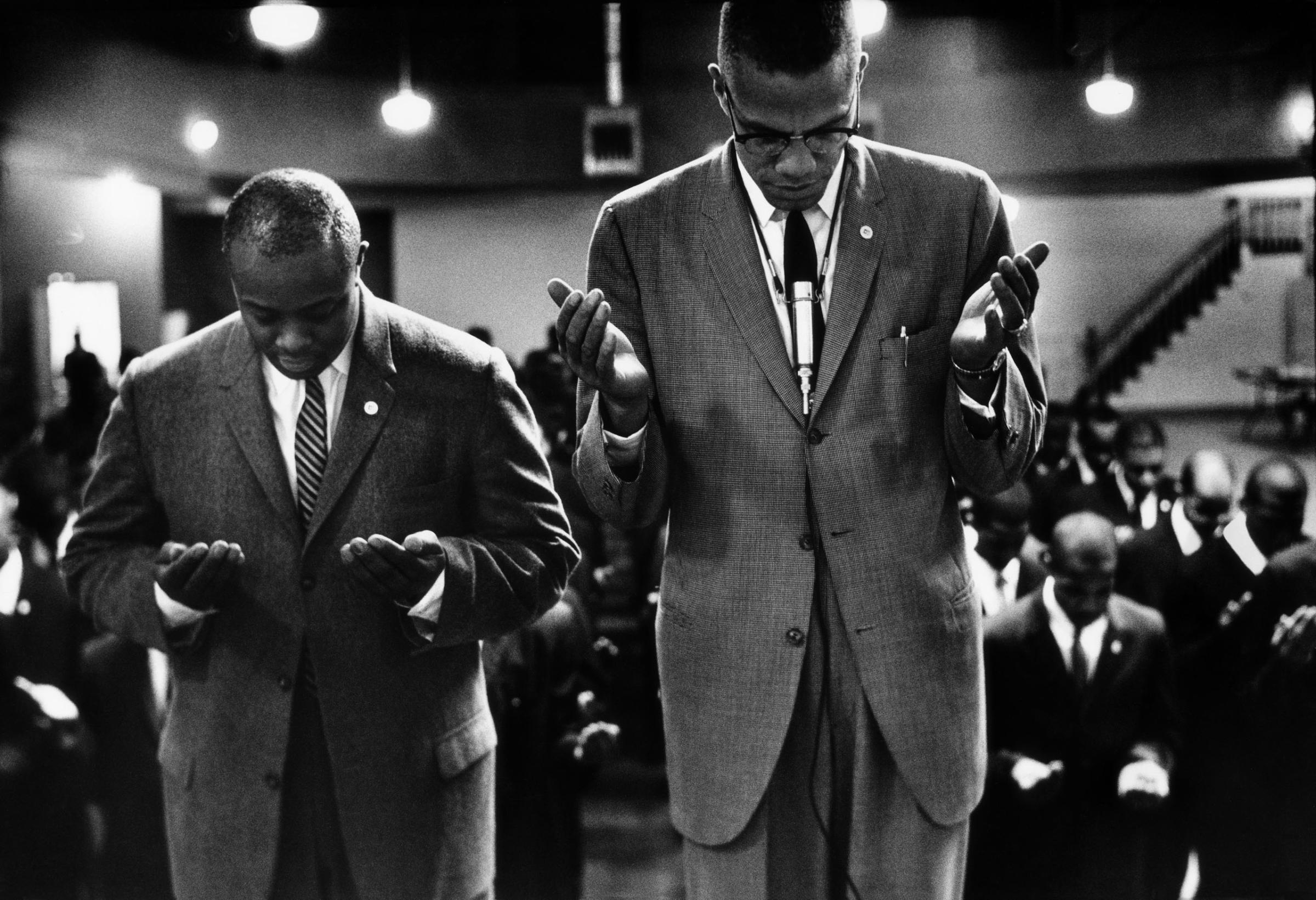

Some of his most famous photo essays depicted black Muslims — with guidance from Malcolm X — and the life of the Fontenelles, a typical Harlem family; so many readers were moved by the family’s struggle to make ends meet that they sent in enough money to help the family move into a bigger home in Queens. As photographer Andre D. Wagner recently wrote for TIME, “It’s the dignity of the people that he was able to capture and his ability to get below the skin that made his pictures undeniable.”

How Gordon Parks’ Photographs Implored White America to See Black Humanity

But it was a different venture from the elder Parks that opened the door for Super Fly: Shaft.

Along with its sequel Shaft’s Big Score, the movie launched a “wave of eminently commercial movies by blacks about the black experience,” TIME reported in the April 10, 1972, issue. As TIME reported back then, Shaft cost $500,000 to make, but grossed an “astonishing $13 million in the U.S. alone,” making it “one of three movies that made any profit for MGM” in 1971. The success showed that “Hollywood finally took note of two basic facts: first, with movie theaters clustering in big cities and whites moving to the suburbs, the black sector of the moviegoing public was growing rapidly (an estimated 20% in the past five years),” TIME reported. “[S]econd, the black audience was hungry for films it could identify with, made by blacks, with black heroes, about black life. Now every major studio is making a play for the big black market.”

Parks Jr., who was also a photographer and got his start in film by watching his father make The Learning Tree, died tragically at the age of 44 in a plane crash in 1979 in Nairobi. But the film genre that he and his father pioneered endured and became controversially known as “blaxploitation.” TIME defined the genre in 1984 in a story about the dearth of roles facing black actors:

As history indicates, it could be worse, and it has been. In D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), the major Negro roles were played by whites in blackface. Hollywood’s first black star, Stepin Fetchit, fitted the stereotype of the slow, sly, shuffling Negro. Meanwhile, the industry mostly ignored Paul Robeson (too strong, too smart, too sexy, too damned uppity) and denied Lena Horne her best potential movie roles, as the mulatto heroines of Pinky and Show Boat, handing the parts instead to Jeanne Crain and Ava Gardner. It was not until the rise to stardom of Sidney Poitier in the 1950s that blacks had a bankable movie hero. “To this day,” argues Film Historian Donald Bogle, “Poitier remains the most important black actor. The image he presented made white audiences take black Americans seriously, at least while they sat in the movie theater.”

Outside the theater, blacks were becoming hard to ignore, and their impact was refracted on the screen. “When schools were being desegregated,” recalls Danny Glover, a likely Oscar nominee for his performance as the hobo in Places in the Heart, “you saw Poitier become a film star. And in the wake of the Watts riots and the push for community control, you got blaxploitation.” These were the low-budget gangster and horror movies that, along with prestige efforts like Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues, detonated the explosion of black films in the early ’70s. Suddenly directors like Gordon Parks and Melvin van Peebles had broken the color barrier, and Cicely Tyson and Diana Ross were crossover stars.

But the moment faded in the 1980s, leaving many African-American actors struggling to find good roles.

Part of the reason for that shift was the controversy that surrounded the genre. TIME said as much a decade earlier in its original review of Super Fly, which the magazine headlined “Racial Slur.” The review argued that the film only exacerbated the problem of perpetuating stereotypes because its characters were “diddy-boppers or street-corner hustlers,” and that Super Fly and movies like it “demean the audiences they are made for.”

Representation of minorities in films and in all ranks of the film-making process is still an issue. While the 2018 SuperFly has a slicker and “practically bourgeois” feel, TIME’s Zacharek writes in her review, the real world outside the fictional movie has similar problems to those faced in earlier decades. “Racial inequality has perhaps shifted forms, but has in no way eased,” she writes. “We might enjoy [the 2018 SuperFly] more if we weren’t stuck in such a place of uncertainty and anxiety.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com