Koko the gorilla earned her pronouns a long, long time ago. It is one of humanity’s great vanities that we withhold pronouns from most animals — or at least we withhold the good ones. Homo sapiens get the dignity of a “he” or a “she.” We fob off other species with an “it.” We speak of the woman who walked down the street, and the dog that accompanied her.

It was never that way with Koko, the celebrated western lowland gorilla who died peacefully in her sleep on June 19, at age 46 — a bit longer than the 30 to 40 years her species typically lives in the wild. From the time she was born, on July 4, 1971, the people who knew Koko and cared for her made sure she was a she. And when the rest of us spoke about her in the years that followed, the very nature of the things we said demanded that we show her the same linguistic respect. It was the rare person who would think of describing Koko as “the gorilla that understands 2,000 words and can sign 1,000 of them.” Those accomplishments fairly demand a who.

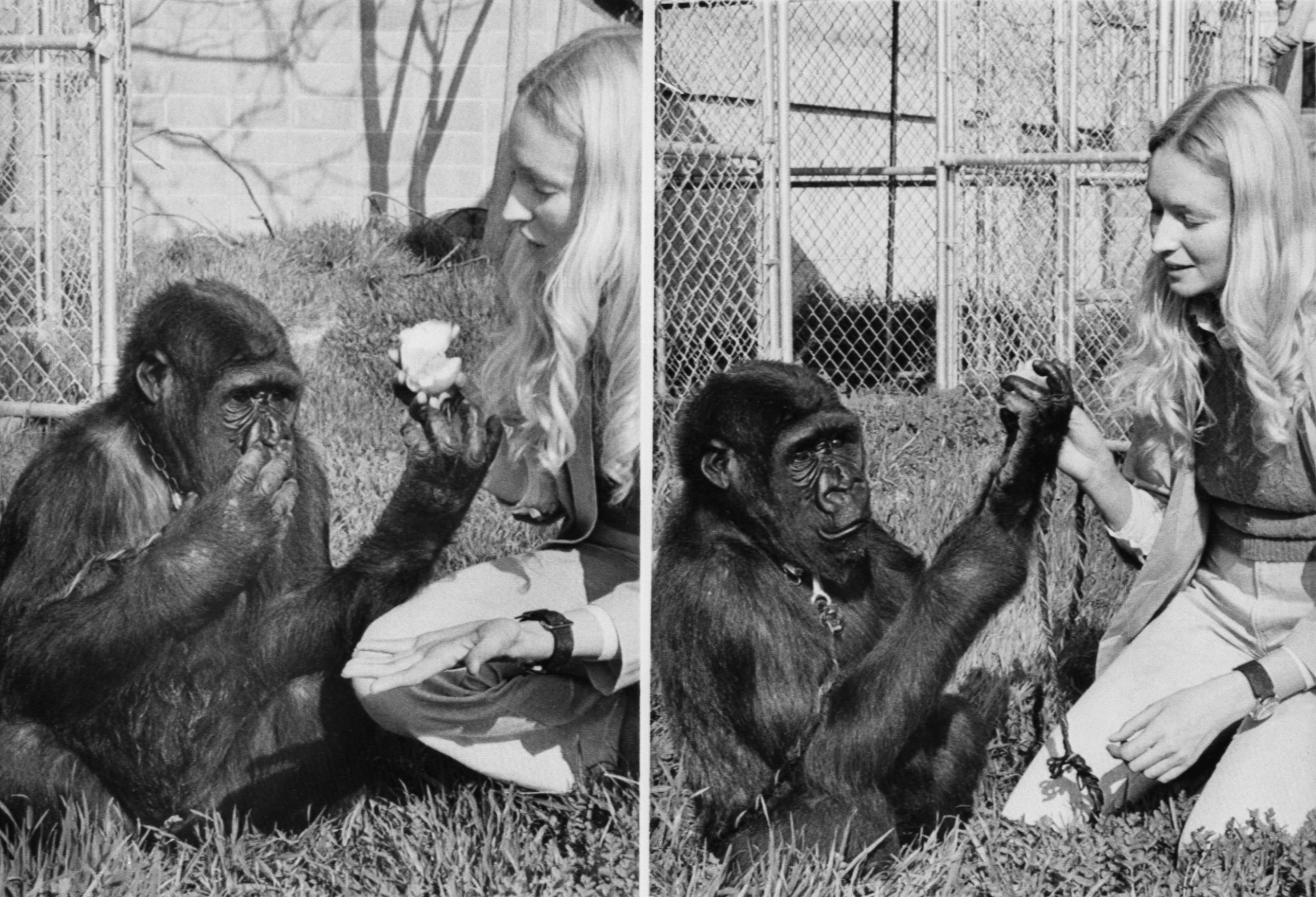

Koko first came to most people’s attention forty years ago, when she appeared on the cover of National Geographic, taking her own picture in a mirror, and we fell for her talents and her cross-species charm straightaway. When she was a year old, Koko began working with Francine “Penny” Patterson, then a doctoral candidate in developmental psychology at Stanford University, who had long believed that there was more to animals—and perhaps a bit less to humans—than we had always believed.

Over the millennia, scientists and philosophers who could not deny that animals appeared to have emotions, thoughts and inner lives could still draw a bright line between them and us thanks to language. It took a great, complex, even divinely blessed mind to encode actions and objects into sounds and words that were then turned into a working language. Show me an animal that can talk and I’ll admit that maybe we’re just one more species in a world full of them. Until then, beasts are merely beasts.

Patterson’s wager — the correct one — was that part of what made us so special was simply that evolution spotted us the hardware of speech: vocal cords, a palate, a tongue and lips that could produce such an infinitely varied array of sounds. If animals had something like that, they could express themselves, too. And while they may not give us Beowulf, they could at least make their thoughts and feelings known. So Patterson worked with what Koko did have — her dextrous, expressive hands — taught her American Sign Language, and with that opened the door to an extraordinary mind.

It wasn’t just that Koko knew her nouns — toy and apple and dog and cookie. She did know hundreds of them, but for all animals nouns are the low-hanging fruit — solid objects that can be associated with labels. More impressive were the verbs; more impressive still was the language of mood and emotion and spatial relations — more and sad and in and stupid and please and hurry and out. And there was also mine — a primitive idea for both animals and humans, signaling, as it so often does, greed or aggression or indifference to others, and yet an idea nonetheless that no animal before had ever been known to grasp abstractly.

Most remarkably — and most poignantly — were the thoughts and sentences Koko built. “You key there me cookie,” she signed to Patterson, instructing her to unlock a cabinet and bring a treat. It was impressive enough for the clarity of its meaning, but there is also the use of the imperative “you,” silent and implied in human sentences, expressed in Koko’s. And there is the “there,” the designation of a point in three-dimensional space.

In 1984, when Koko’s kitten, whom she named “All Ball” was hit by a car and died, she mourned openly. “Cat, cry, have-sorry, Koko-love, unattention, visit me,” she signed. She expressed her grief in more or less the same way we would—and she apparently experienced it in exactly the same way, too.

After Koko breached the language berm that we thought separated us from all other species, more animals have come across. There is Kanzi, the 37-year-old bonobo who can understand hundreds of lexigrams representing words and actions, and can construct sentences by pointing out the correct symbol on a screen. There is Chaser, the 14-year-old border collie, who knows the name of 1,022 objects and can retrieve them on command. There was Alex, the 31-year-old gray parrot, who died in 2007 with a vocabulary of 150 words and the same ability as Koko and Kanzi to assemble them into thoughts and sentences.

It was Alex, whose lexicon was smaller than that of the other expressive animals, who may have thrilled — and spooked — us the most. He not only knew his words, he could speak his words. A parrot who mimics without understanding is an amusement. A parrot who knows what he’s saying as he says it is an intelligent agent with a working mind.

That, of course, is true to a degree of all animals — or at least all higher animals. If we can no longer plausibly claim that language elevates us uniquely among the beasts, we can at least say it lifts every animal who can learn it well over every animal who can learn it less well, and over all animals who cannot learn it at all. That may not make the lives of the language-savvy animals more worthy, but it does make them richer. By that measure, Koko, in her long 46 years, lived richly and well indeed.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com