Senator Ron Johnson sits across from me on board the Ronmobile, explaining why his opponent is to blame for all the crime in Wisconsin. “I can’t tell you how dispiriting the whole defund-the-police movement is,” he says, leaning both forearms on the fold-down Formica table at the front of his dark-green campaign RV. “The revolving door in our criminal-justice system. Police risk their lives to apprehend a criminal, and then district attorneys just let them out. Why are we doing this?”

Johnson ticks off a spate of liberal criminal-justice reforms that have been enacted in Wisconsin and other states in recent years: declining to prosecute low-level offenders, eliminating cash bail, prohibiting police chases. Policies like these, he argues, have created a climate of impunity that leads to chaos, particularly in urban areas. Police, he says, feel demoralized and undermined by a sense of suspicion and criticism. “People don’t want to throw away their life, their career, their retirement by engaging with criminals that maybe will resist apprehension,” he says. “You start having something that doesn’t look very good on camera, and they’re afraid that, well, doing my job could ruin my career. So what do they do? They back off. They don’t police the way they’ve been taught to police. They don’t police the way they’d like to police.”

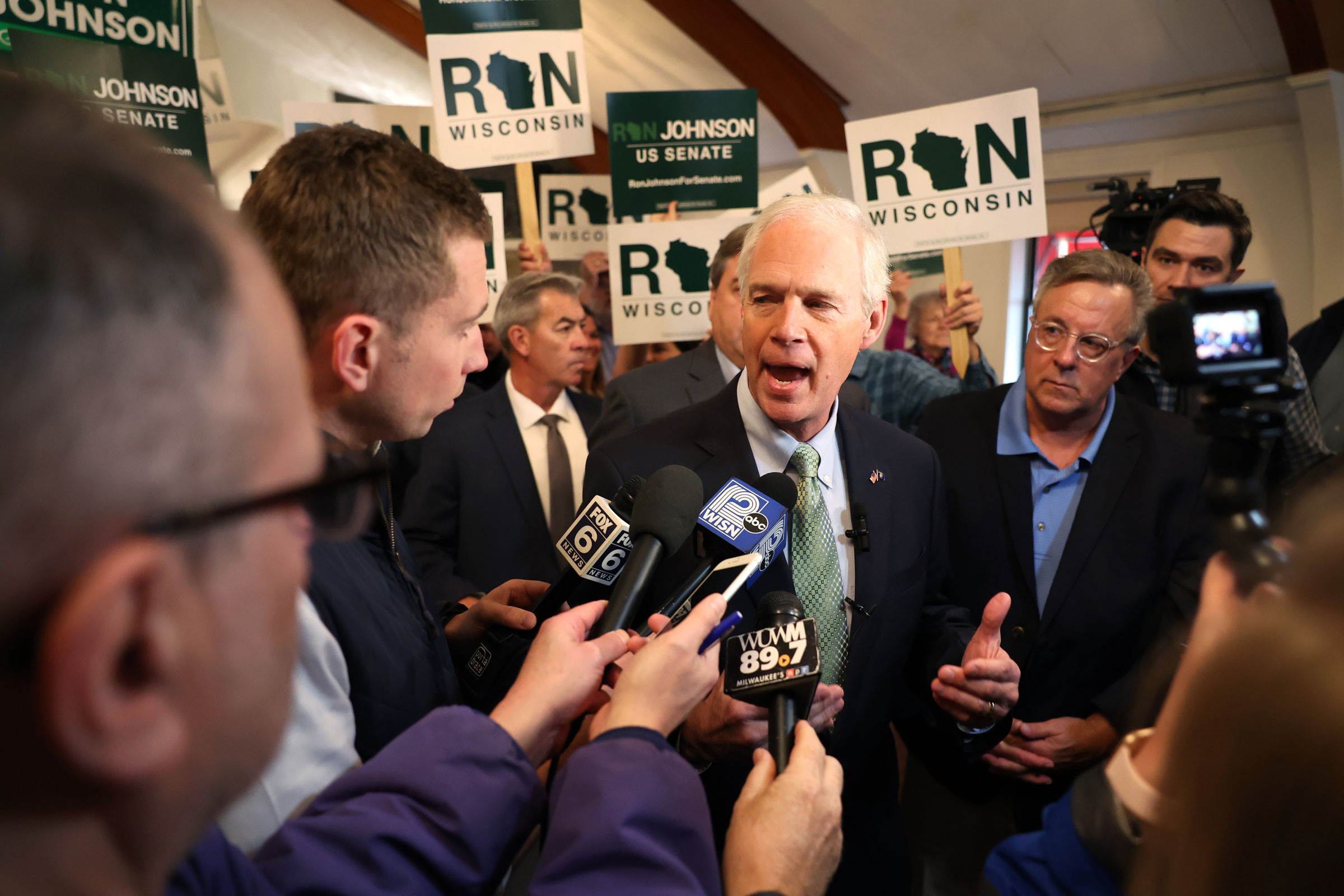

Johnson is the most unpopular senator on the ballot this year, with a penchant for conspiracy theories and odd utterances. He has held Senate hearings showcasing COVID-19 vaccine skeptics and participated in the plot to replace President Biden’s electoral-college votes with “fake electors.” In Washington, even many Republicans view him as a loner and a crank. Going into this election cycle, Democrats saw him as a top target and hoped to unseat him in a state Biden narrowly won in 2020. Yet as the 67-year-old Republican seeks his third term, the argument that liberal policies and attitudes have led to out-of-control crime could lift him to victory in his campaign against Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes, a 35-year-old progressive who would be the state’s first Black senator.

Johnson and his allies have spent millions on attack ads targeting Barnes for his past statements and record on criminal justice. The ads invoke horrific crimes and tie Barnes to the days of unrest in Kenosha after a police shooting in August 2020. They’re echoed by the nightly news, which reliably features a litany of lurid crime reports, and the lived experience of urban and suburban residents, who increasingly fear leaving their homes after dark. In a recent Marquette University Law School poll, which found Johnson leading Barnes by two percentage points, 85% of respondents said they were concerned about crime, and 48% of Milwaukee residents said they did not feel safe going about their daily lives.

“There’s gunfire every day,” says state Representative Dan Knodl, a Republican who represents exurban Germantown, where Johnson and I spoke. “Many people moved from the cities to the suburbs because of the criminal element in their neighborhood. But now we see the criminal element is expanding out of the cities into these suburban areas.” The problem, he says, is a “revolving door policy” in the criminal-justice system, with prosecutors and judges who let criminals go or give them light sentences after they’re arrested, putting them back on the streets to commit more crime.

Wisconsin isn’t the only place where these arguments have found traction. Across the U.S., crime has become the defining theme of the midterm elections. It’s the top subject of campaign ads: Republicans have spent $100 million on crime-focused ads against Democratic candidates nationally, $20 million more than they’ve spent on ads about inflation, and Democrats have poured nearly as much into their own ads on the topic. The accusation that liberal policies have allowed crime to get out of hand has hobbled Democratic candidates from Pennsylvania to Nevada and made elections competitive in surprising places like Oregon and New York state. A Gallup poll released last week found 56% of Americans believe crime is increasing in their area, a five-decade high. For all the talk about economic angst driving this year’s Democratic backlash, 2022 is really a referendum on this: the chaos and disorder people see around them; the fear and lack of control they feel as a result; and who or what they hold responsible. It’s a brutal irony: two-and-a-half years after anger at police brutality spurred worldwide protests and galvanized a bipartisan movement to liberalize the criminal-justice system, the near-term legacy is a return to law-and-order, tough-on-crime politics.

Before we boarded the bus, Johnson spoke to a few dozen local supporters in an office-complex parking lot adjacent to a roaring highway in an exurb a half-hour north of Milwaukee, informing them that his opponent hates America.

“How can you not love America? How can Mandela Barnes not love this country?” Johnson told the crowd. He mentions a 2015 tweet in which Barnes invoked the Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s support for Black Lives Matter; a 2016 Russia Today appearance in which Barnes “rationalized” the shootings of two cops in Dallas; a 2018 interview in which Barnes characterized Wisconsin as home to “concealed carry racism,” more insidious than the overt form found in the South. “Why does he want to be your Senator, representing Wisconsinites, if he has such disdain for us?” Johnson says.

Johnson rejects the accusation that there are racial undertones to this argument. “I’m just telling the truth,” he tells me. “There’s nothing racist about telling the truth.” The truth, in Johnson’s view, includes the “Ferguson effect”—the hypothesis that police have become afraid to do their jobs because they fear being prosecuted or criticized. It includes the idea that the 1960s War on Poverty backfired by creating dependency and incentivizing out-of-wedlock births, depriving young men of the father figures and discipline they need. “A lot of our policies have driven the breakdown of the American family,” he says. “If you want to reduce crime, you have to have strong families with two loving parents.”

These assertions are hotly contested by liberals and criminal-justice experts. They insist that rising crime is more perception than reality, and that its causes can’t be traced to “soft on crime” policies or progressive prosecutors. But it is undeniably true that the political ground has shifted. The last decade has seen a widespread liberalization of criminal-justice laws, accelerated by the racial-justice protests of 2020. Biden, who authored the 1994 crime bill, was forced to apologize for it during the 2020 primary, and these days when he speaks about crime he mostly talks about gun control. Aiming to rebut the “defund” accusation, House Democrats in September passed a measure to give $60 million to local police departments, an initiative that was nearly derailed by progressives’ objections. Unable or unwilling to reject the demands of an activist base animated by a deeply felt sense of injustice, liberals have broadly embraced policies and rhetoric that are skeptical of policing and incarceration as solutions to crime and disorder. Now they have no good answers for an electorate clamoring for protection and safety.

Barnes is a product of this dynamic. The candidate’s liabilities were widely known in Democratic circles, party insiders say, and in the primary he faced several more moderate candidates who suggested that they would fare better in the general election. But they feared attacking Barnes’s record and positions would spark a backlash from the Democratic base, damaging their own political future while potentially hobbling Barnes.

“I spent months trying to warn people,” says the Milwaukee-based political commentator Charlie Sykes. In his previous life as the state’s most powerful conservative talk-radio host, Sykes was almost singlehandedly responsible for Johnson’s entry into politics, introducing him to the state’s GOP power structure after hearing the plastics-company CEO speak at a 2010 Tea Party rally. Sykes left the GOP over Trump and is now a leading Resistance figure, with a bestselling book and an MSNBC contract. He would love to see Johnson defeated. “He ought to be the most vulnerable Republican incumbent,” Sykes says, “yet I think he’s likely to be re-elected because the Democrats have nominated somebody who is a very difficult sell to swing voters in Wisconsin because of his positions on criminal justice.”

In columns and commentaries over the past year, Sykes tried to alert Democrats to their “Kenosha problem” in the state and to Barnes’s baggage specifically. But “Democrats are reluctant to offend their base by going there on issues like crime,” he says. Just as Republicans face the wrath of their voters when they speak hard truths about Donald Trump and the 2020 election, Democrats’ liberal base doesn’t want to hear how unpopular their stances on crime and policing are with the general electorate, and will turn on politicians who bring it up.

And so, rather than address voters’ anxieties, Democrats too often try to talk them out of those concerns, leaving many feeling gaslit and accused while Republicans assure them that their fears are valid and something should be done. “The denialism is not helping,” Sykes says. “People bring out the charts and say, oh, it’s not up that much, or it’s nothing compared to the ‘90s. That’s not the reality that voters are thinking about right now, and that kind of response just plays into the narrative that they don’t get it.”

In our interview aboard the Ronmobile, Johnson tells me he had no choice but to make this the central issue of the campaign. “When people don’t feel safe in their homes, or safe to leave their home and go down to the drugstore, what else can you do?” he says. Johnson remains the rock-ribbed ideologue that so endeared him to the Tea Party. His view, he explains, is that the government’s job isn’t to solve all our problems but to preserve our freedom and liberty. (When he signs autographs for supporters, he writes, “Fight for freedom!”) But none of that matters, he says, if people don’t feel secure. “You can’t have a functioning economy if you don’t have safety in the streets,” he says. “You have to have safety and security to have any kind of successful society.”

The ads are ubiquitous and unsubtle. As I pilot my rental car back to Milwaukee, radio dial turned to 620 AM—WTMJ, the station that was once home to Charlie Sykes—they come up every few minutes.

“Violent crime in Wisconsin has increased at nearly double the national average,” a breathy female narrator says, a siren audible in the background. “Homicides up 70%. 315 murders just last year. Who can we trust to keep us safe? Not radical Mandela Barnes.” In late October, Darrell Brooks, a 39-year-old with a history of anti-semitic and anti-white social-media posts, was convicted of killing six people after ramming his SUV into a suburban Milwaukee Christmas parade last year, two weeks after being let out on $1,000 bail in what the county’s progressive district attorney later said was a mistake.

“Even after the Waukesha Christmas parade attack, Barnes doubled down on eliminating cash bail, releasing criminals back into our community,” the ad says. “He even bragged about letting convicted criminals out of jail.” Here the ad plays a recording of Barnes, at a 2018 conference, telling an audience, “Reducing prison populations is now sexy.”

“Sexy?” the narrator asks indignantly. “Releasing criminals isn’t sexy. It’s dangerous. The stakes are high, too high to risk on defund-the-police radical Mandela Barnes. He won’t keep your family safe.”

WTMJ’s midday host, Jeff Wagner, is worked up today about a different racially tinged crime. While minor in terms of charges, it illustrates some of the issues at hand. On Oct. 10, a 62-year-old white man, Robert Walczykowski, thought he saw some youths stealing bicycles from his neighbor’s yard. As he called the police, holding his phone to his ear with his right hand, he used his left hand to grab one of them by the neck. A witness recorded the incident, which went viral and led to a neighborhood protest. The bikes were later found in the home of the mother of the young man, a 24-year-old with severe disabilities. The young man was not injured and left before the police arrived. On Oct. 27, prosecutors charged Walczykowski with disorderly conduct.

To Wagner, a former federal prosecutor and onetime GOP candidate, the whole situation seems upside down. “What can we gain by prosecuting the 62-year-old man for disorderly conduct for presumably seeing a crime in progress and at least trying to detain temporarily, while he’s calling the cops, one of the people who he feels, correctly or incorrectly, may have been involved in this?” Wagner says. “They look the other way on so many crimes—real ones—and then they go after this guy? Give me a break. You run afoul of the woke prosecutors in this town, you’re the one who ends up being the criminal.”

Read More: The Fight For Latino Voters in Nevada Is the Future of American Politics.

I pull up to the squat brick building that houses the Milwaukee Police Association, where Andy Wagner (no relation to Jeff Wagner) sits in front of a light-blue wall lined with photos of dead cops. Each framed plaque has the officer’s black-and-white photo on one side, his badge on the other. Above them are the words “ALL GAVE SOME. SOME GAVE ALL.” In the hallway outside are stacks of yard signs for candidates the union has endorsed, all of them Republicans.

Johnson won the union’s endorsement by pledging to support police funding as long as it was not attached to other spending he considered wasteful. Barnes, says Wagner, the association’s president and a 25-year veteran of the force, never sought the endorsement at all. The union used to endorse Democrats too, he tells me. But not lately. “We have seen some Democrats say that they enjoy the police and they want the police,” he says. “But when they get into the statehouse and those bills come up to support the police, they are always on the opposite side.”

In May 2020, as the George Floyd protests swept the nation, protesters in Milwaukee blocked traffic, surrounded police stations and painted “defund the police” on the street in front of City Hall. Then, a few months later, in Kenosha, an industrial lakefront town 45 minutes to the south, a woman called the police on her boyfriend, who she said had come in her house without permission and was trying to steal her car. The cops tased 29-year-old Jacob Blake twice, but he continued to charge toward them, holding a knife. As he opened the door to a car with three children in the backseat, Officer Rusten Sheskey shot him seven times in the back. Blake was severely injured but survived.

The shooting, recorded on video, immediately stirred outrage. Protesters took to the streets. Barnes gave a speech in which he accused the officer of deliberately escalating the incident, which he termed “not an accident,” adding, “This felt like some sort of vendetta taken out on a member of our community.” Governor Tony Evers, also a Democrat, called Blake “not the first black man or person to have been shot or injured or mercilessly killed at the hands of individuals in law enforcement in our state or our country.” He called on the legislature to pass a slate of police reform in response.

As Kenosha erupted, it took Evers two days to send in the National Guard and four days to visit the city. In the meantime, a white teen from Illinois, 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse, traveled to Kenosha with an AR-15-style rifle. Chased by white protesters grabbing for his gun, Rittenhouse shot and killed two and wounded another.

Though many liberals recall these events as instances of police brutality and racial double standards, Wagner sees two tragic but justified shootings—a conclusion supported by the justice system. Sheskey was cleared of excessive force by local, state and federal authorities as well as an independent review; Rittenhouse was acquitted by a jury that found he was acting in self-defense. “If some armed man was going to take my three children, I would want the police to act the exact same way, and make sure that he’s not leading them on a 100-mile-per-hour police pursuit with my kids in the back of the car,” Wagner says. “So I think the officer acted appropriately, and I wish the governor would have waited for all the facts to come out.”

The Milwaukee police department, Wagner says, is more than 250 officers down from 2018 staffing levels. Court closures due to COVID-19 created an ongoing backlog and led judges to immediately release misdemeanor arrestees. A 2018 settlement with the ACLU requires officers to document every incident of stop-and-frisk. Under one recently repealed policy, police stopped engaging in car chases for any reason. While the eye-popping murder numbers make headlines, people are just as affected by the explosion of lower-level quality-of-life crimes. Car thefts have more than doubled since 2020, reaching more than 4,000 already this year, many at the hands of a gang called the “Kia Boys” who terrorize the city with their reckless joyriding.

All the liberal talk of addressing the “root causes” of crime is nice, Wagner says, but it doesn’t do anything for those being victimized today. “99.9% of the people in these communities wake up and go to work every day, they want to go home and not have drug dealers on their porch,” Wagner says. “They want to make sure that their car is safe at night, and they want to just live their life without having to fear crime for walking down the street.” But these days, he says, politicians seem more concerned with the well-being of criminals than with their victims.

Come campaign season, politicians like Barnes say they support the police after all, Wagner says. “They may say they have had a change of heart,” he adds. “But it’s not easily forgotten what they did two years prior.”

Across town at City Hall, Milwaukee’s mayor, Cavalier “Chevy” Johnson, sits in a large wood-paneled office lined with family photos and sports memorabilia. A 35-year-old Democrat, Johnson became the city’s first elected Black mayor in April. The day after we meet, he will introduce former President Obama at a rally alongside David Crowley, the 33-year-old first Black Milwaukee County executive, and Barnes: a whole rising generation of dynamic, young Black leaders.

Johnson grew up in Milwaukee’s notorious 53206 ZIP code, home to the highest percentage of incarcerated Black men of any ZIP code in the country. One of his brothers runs a jail in which another of his brothers is a prisoner. “Crime and how campaigns use it, in terms of translating that into fear, is an effective tool, one we’ve seen used in campaigns going back as far as anybody can remember,” he tells me. “I don’t think that’s anything new.”

To Johnson, the wall-to-wall GOP ads are a cynical ploy to use racially tinged fear to scare suburban and rural residents and pit them against the big, bad city. It’s particularly rich, he says, coming from a Republican Party that’s just committed to hold its 2024 nominating convention in Milwaukee. “Republicans at nine o’clock in the morning say, ‘Milwaukee is a terrible hellscape, and if you go into the city limits, your head’s going to get blown off,’” says Johnson, who worked with Ron Johnson and other Republicans to land the convention, to some liberal criticism. “And then at three o’clock they say, ‘We’re so lucky and fortunate to be coming to this great city where we’re going to nominate our nominee for President of the United States!’”

The mayor insists that the idea that crime is rising is partly a media illusion. It’s easy, he says, for local television news to report on sensational crimes without putting them in context. “What’s the old saying—if it bleeds, it leads?” he says. But in fact, he notes, while homicides have continued to rise, crime overall has ticked down 14% from last year.

Nonetheless, Johnson doesn’t deny that more needs to be done. Shortly after George Floyd’s murder, Johnson, then the head of the city council, pushed to have Milwaukee apply for a federal COPS grant to fund the hiring of more officers. In the wake of the protests, the idea was controversial, and the city council rejected it. But Johnson twisted arms behind the scenes, got the proposal resurrected, and eventually won passage of it—to the chagrin of activists on the left. He is a man caught in the middle. “Public safety is a concern, including to people of color in Milwaukee,” he says. “In my majority African American district that I represented, they wanted police there too. They just want police that police constitutionally and fairly. It’s not that they don’t want officers.” Milwaukee has a long history of police shootings, including the 2016 killing of an armed Black man that led to days of violent unrest.

Read More: Jim Clyburn’s Long Quest for Black Political Power.

Democrats, Johnson tells me, need to do a better job of telling their story and making people feel safe—getting the message out that they are simultaneously fighting for more and better policing alongside programs to address the root causes of crime and poverty. “Has defunding the police really happened in any city? No,” he points out. (Even in Minneapolis, the liberal city council’s post-Floyd pledge to disband the police department was shelved after a public backlash.) “And cities, by and large, are run by people who are Democrats. So Democrats should stand up and say, hey, we’re the ones that are supporting law enforcement, we’re the ones that are keeping the cops on the beat, in cities across the country.”

Johnson and Barnes are good friends who have known each other for more than a decade. It galls the mayor to hear the way his friend is being attacked. “I’m the mayor of the largest, most diverse city in the state,” he says. “Most Black people, most people of color, generally in the state of Wisconsin, they live here in my city, the city from which Mandela Barnes hails. If he was interested in defunding the police, with our long history, I would think that he would have called me. That hasn’t happened. It’s a complete misrepresentation. What Mandela has talked about is making sure that we have support and funding for police. But then also, we’re going to make sure that we have resources in our communities, so that folks aren’t in a position where you need so many police.”

Kenosha burned for days, but today there are few obvious remnants of what happened. Nothing commemorates the protests in Civic Center Park, the central square by the jail and courthouse that were once surrounded by protesters. In the Uptown neighborhood, a charred building features a discreet hand-painted Black Lives Matter slogan. “I think we’re healing,” says Ricardo Lebron, president of the local firefighters’ union, which has endorsed Barnes. “You still see some of the blighted areas, but it wasn’t like the whole city burned down.”

Lebron and I are speaking at a union hall on the outskirts of town, where Barnes and the rest of the Democratic ticket have come to rally the troops. A stocky white man in a maroon fleece jacket, he says he’s tired of seeing the city’s pain exploited and distorted by political attacks. “There’s a lot of false information out there, saying they didn’t give us the help, they didn’t protect us,” Lebron says. “We were on the front lines. The National Guard was there. Our mayor, our county executive, our county sheriff—they all say that everything they asked for, they got it.”

A few dozen people have gathered in the large, linoleum-floored room, lit by fluorescent ceiling panels and bisected by an accordion divider. There’s a mix of local Democratic activists and union members. Big white guys in overalls and flannel mingle with youths with facial piercings and women with BANS OFF OUR BODIES totes. Barnes takes the stage in a maroon puffy vest, checked shirt and jeans. “I’m so happy to be back here in the house of labor, because I was born in a house of labor,” he says. “And I absolutely would not be here if it were not for the opportunities of American manufacturing and the strength of Wisconsin labor unions.”

Barnes’s campaign has stressed this message of working-class solidarity and economic populism, with ads touting him as a champion of “Wisconsin workers.” It’s a message that draws a contrast with Johnson’s wealth while also subtly jabbing at the common assumption that “blue collar” means “white.” In fact, as his story shows, people of color have always formed part of the backbone of the working class.

The lieutenant governor is an engaging speaker with a nervous edge; he tends to jam one hand in his pocket while holding a microphone with the other. The only child of a schoolteacher and assembly-line worker, Barnes attended public schools in Milwaukee and the historically Black Alabama A&M University, then went to work in social-justice organizing and Democratic politics. In 2012, he ran for state assembly, successfully challenging an incumbent Black Democrat for a seat representing the city’s urban North Side. Barnes challenged the incumbent from the left in the primary, arguing it was time for a new, progressive generation of leadership.

That year, Obama won Wisconsin even as Democrats failed to oust Republican Gov. Scott Walker in a recall. Walker’s attacks on labor unions weakened Democrats in the state, and in 2016 Hillary Clinton became the first Democrat to lose Wisconsin since Walter Mondale in 1984. Barnes, who supported Bernie Sanders in the 2016 and 2020 presidential primaries, ran for the state senate in 2016, again challenging a Black longtime incumbent, but this time he lost. The party made a comeback in the Trump era. In 2018, Walker sought a third term and Evers, a mild-mannered former school superintendent, narrowly defeated him. Barnes was elected lieutenant governor, becoming the second Black statewide elected official in Wisconsin history.

In this year’s Democratic Senate primary, Barnes was the favorite from the start. The field included businessman Alex Lasry, whose father owns the Milwaukee Bucks, and state treasurer Sara Godlewski, also a multimillionaire. A few weeks before the Aug. 9 primary, both dropped out and endorsed Barnes, saying they saw no path to victory and wanted to unite the party. The campaigns’ testing, say party insiders familiar with the matter, showed Democratic base voters would react negatively to attacks on a dynamic young Black man for being anti-police.

In Kenosha, I ask Barnes whether he now believes the Jacob Blake shooting was justified. He declines to directly answer. “What happened here was an unfortunate tragedy that should never happen again. I stand by that,” he says.

Barnes’s exasperation with the way the campaign has developed is evident. “I’ve lost friends to gun violence, more friends than I care to count,” he tells me. “This is something that’s deeply personal to me. It’s why I got involved in the first place, to make communities safe. So I certainly hear everything people are saying and I sympathize with them.” But Johnson, he charges, has no plan to improve the situation. “People like Ron Johnson have pointed fingers, but they have not lifted a single one of those fingers to help us out when it comes to issues regarding crime,” he says. “They totally neglected communities that have been starved of resources and jobs, they totally neglected our schools. And they’ve also abdicated their responsibility to provide communities with the funding to help local governments do what they need to stop crime and respond to crime.” What’s needed, Barnes says, is a “comprehensive solution” that includes law enforcement alongside programs to increase opportunities for jobs and education, making crime less attractive to underprivileged youth.

Politicians like Johnson, Barnes says, are exploiting people’s pain to score political points. “There’s a very real contempt that people like Ron Johnson have for neighborhoods that have been under-resourced and undervalued,” he says. “The situation that keeps people up at night, the situation that people live and experience in real time—they use it, they talk about it for political gain instead of showing up to actually have conversations with the folks who are dealing with these challenges. That’s what gets me mad.” The ads about the Waukesha Christmas parade attack are “disgusting,” he says, and have re-traumatized the victims of the attack. They’re also inaccurate: the cash-bail reform that Barnes supports never passed; it was the current law that allowed Brooks out on bail. “The bill that I supported, so that people don’t just get to buy their way out of jail, that makes communities more safe,” he contends. “The current system isn’t safe.”

Back in inner-city Milwaukee, Angela Lang sits behind a desk in a cluttered office over a street-corner church. Banners on the walls read “JOY IS AN ACT OF RESISTANCE” and “GOD IS A BLACK WOMAN.” A stack of fliers in the corner advises people with criminal convictions how they can determine if they are eligible and register to vote. In 2017, Lang founded BLOC, Black Leaders Organizing Communities, a grassroots social-justice group. The years since have been difficult, but the organization has grown to a staff of 65 and is working to turn out Black voters for this year’s Democratic ticket, including Barnes, whom she sees as an ally. “We are not surprised that crime has become such a focal point of the election,” Lang says. Given what happened in Kenosha, “we knew this was going to be weaponized. I just don’t think we knew how bad it was going to be.”

Lang would like to see Milwaukee devote less funding to the police force, which currently eats up a significant portion of the city’s budget and isn’t directly accountable to the elected council. (BLOC did not support Mayor Johnson in his recent election, viewing him as insufficiently progressive.) “People hear the word ‘defund’ and they don’t want to have the conversation at all,” she says. “We should always be talking about what true safety looks like. What does it look like to not have these bloated police budgets, where law enforcement is responding to things like mental-health crises?” Investing in mental-health services, housing and education needs to be part of the discussion, she says. “What keeps us safe is making sure that people’s basic needs are being met.”

For most of September, as Republicans pummeled Barnes with crime-themed attacks that his campaign lacked the funds to respond to, anxious Democrats watched Barnes’s poll numbers plummet and fretted that he wasn’t doing enough to fight back. When BLOC’s organizers knocked on doors in their neighborhoods, they found many voters who were discouraged or even swayed by the ads. But now, she says, “we’ve seen more and more excitement. We’re seeing more and more yard signs, in neighborhoods that typically wouldn’t have yard signs.”

Lang is chagrined at the way the conversation around police reform, which seemed so promising in the wake of Floyd’s murder, has been, in her view, hijacked and demagogued. In 2018, urged on by Jared Kushner and Kim Kardashian, then-President Trump signed a bipartisan criminal-justice reform bill, which Senator Johnson voted for. But now, two years after people of all races flooded into the streets in solidarity with the Black community, public opinion has soured on police reform and the Black Lives Matter movement, and backlash threatens to erase the political and policy gains.

I ask her whether the movement has moved forward or backward since the protests. “I think about this often,” she says. Whether or not her preferred policies are advancing, she argues, the conversation about these issues has changed, and that represents progress that can’t be taken away. “If you’re a member of a community that is often targeted by the police, sometimes it feels like the change is not happening fast enough,” she says. “It’s a reckoning that we’re having in this country, and it’s going to take a long time to figure out how we move forward. We’re on this precipice where we can go one way or another.”

It’s the day before Halloween, and BLOC is hosting a trick-or-treat for neighborhood families. Lang is wearing an orange cardigan, bright-red skirt and neon-orange tights. Staffers in costumes hand out baggies of candy from a folding table set up on the sidewalk while a portable speaker blasts Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” In one direction, vacant lots stretch into the distance; in the other, the pocked street is lined with run-down wooden houses with sagging porches.

Chris Bland, a 47-year-old manager at Sav-a-Lot, stops by, wearing a black ball cap and hoodie, holding a toddler girl in a tutu and hot-pink jacket. He’s aware of Barnes’s candidacy, though he struggles to remember the candidate’s name. “Mandela, he’s talking the right stuff, but he’s got to show up,” Bland says.

When I ask Bland what issues are top of mind, he immediately says street violence, guns, and carjackings. “The neighborhood is out of control,” he says. The solution, to him, is obvious. “If we had more police, it wouldn’t be like it is right now,” he says. “But it’s the right police we need.”

With reporting by Mariah Espada, Anisha Kohli and Simmone Shah

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Molly Ball/Milwaukee at molly.ball@time.com