COVID-19 changed many things about medicine, not the least of which is how we think about do-it-yourself testing. Before the pandemic, health experts weren’t convinced people would accept, much less embrace, the utility of testing themselves at home for SARS-CoV-2. Pregnancy tests pretty much dominated the at-home testing landscape, although a few recent additions, for conditions like HIV and Alzheimer's, have appeared on pharmacy shelves, albeit with varying levels of confidence from the medical community.

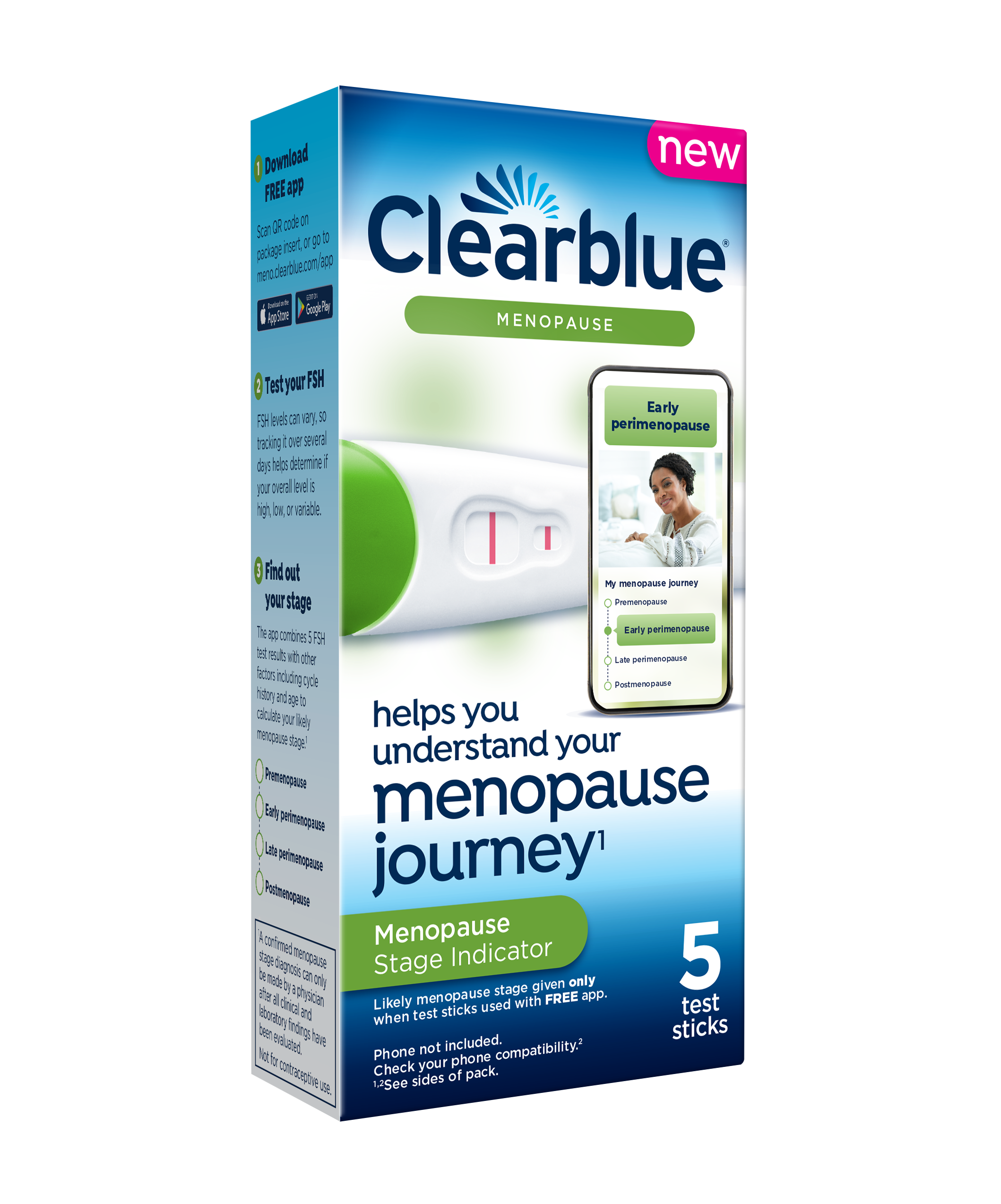

Now Clearblue, the company that makes pregnancy and fertility self-testing kits, launched a DIY test for menopause. The kit, available for $29.99 at major retail pharmacies, requires women to test their urine every other day for a total of 10 days and detects changing levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Over the 10 day span, the Menopause Stage Indicator test monitors a woman's changing levels of FSH and, based on general levels of these hormones calibrated by age, informs her about which stage of menopause she might find herself—premenopause, early perimenopause, late perimenopause or post menopause.

Among women’s reproductive conditions, fertility receives the lion’s share of attention, at least in the public domain. Most women of menopausal age aren’t aware that their changing bodies, and the symptoms that accompany those changes—such as hot flashes, night sweats and irregular menstrual cycles—are a sign of menopause. “We get the talk when we are about to start our periods, at age 10 or 11,” says Dr. Stephanie Faubion, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health and medical director of the Menopause Society who is not involved with Clearblue. “I have patients who have absolutely no idea what is happening when they are in perimenopause or menopause and get a wide variety of symptoms from hair loss to night sweats—it seems confusing and scary.”

An attempt to end confusion about menopause

Clearblue is hoping to address that confusion by giving women the ability to track changes in their bodies themselves. “What we’ve seen from our research is a real need for this product,” says Dr. Fiona Clancy, R&D senior director at Clearblue. “Online, menopause is searched 10 times as much as fertility, and two out of three women feel unprepared for the menopause journey.”

Doctors like Faubion who treat women for mid-life changes, however, aren’t convinced this knowledge is necessary for navigating the menopause journey. Menopause is defined as not having periods for 12 consecutive cycles, and prior to reaching that stage, women can experience varying windows of irregular bleeding in the perimenopause stage, sometimes lasting for years. During those times “lab levels of hormones like FSH are fluctuating all over the place by the day,” says Faubion. “I don’t understand what the benefit [of the test] would be.” She rarely tests women for menopause because hormone levels can vary widely during an individual woman’s cycle, as well as among different women.

As FSH levels increase, another hormone, estrogen, also rises, and together they prompt the ovaries to release the egg each cycle during ovulation. As women approach menopause, estrogen levels start to drop as the ovaries begin to shut down, and in response, the pituitary gland in the brain, which regulates FSH levels, attempts to stimulate the ovaries to produce more FSH and in turn more estrogen. But these levels of FSH are notoriously wide-ranging, not just among individual women during their cycle, but among different women as well.

Read More: Now's the Time to Bring Up Menopause at Work

That’s why instead of depending on lab tests, doctors like Faubion rely on symptoms that patients report. “The diagnosis of menopause and its stages are clinical diagnoses, and we treat by symptoms. So I’m unclear about the utility of the test,” says Dr. Samantha Dunham, co-director of the center for midlife health and menopause at NYU Langone Health, who is also not involved with Clearblue.

Dunham turns to blood or urine tests to check hormone levels during mid-life changes only among women who no longer have regular periods, because they have had their uterus removed either through a hysterectomy or endometrial ablation, or are using an intrauterine contraceptive device that stops regular menstrual cycles. Because these women don’t have periods, doctors can’t use changes in the cycle as an indicator for potential perimenopause symptoms, and turn to lab tests to understand what’s happening with the ovaries and hormone levels.

Questioning the value of a menopause test

For most other women, however, even if they use the test to learn, say, that they are in perimenopause, the results still wouldn’t tell them when they will actually hit menopause. What’s more urgent for women during this time is addressing their symptoms—from night sweats to hot flashes and irregular bleeding. “These numbers always have to be interpreted in the context of the patient, and not just as a plus-minus test,” says Dunham. “A pregnancy test is a plus-minus test—you’re pregnant or you’re not. FSH is not a plus-minus test.”

Both Faubion and Dunham agree that women are armed with less support and education about menopause than they are about the start of their periods. “I think it often catches people by surprise, and happens earlier than they think,” says Dunham.

She suggests women who are experiencing changes in their cycles at mid-life should talk to their primary care doctor about changes they are experiencing, and turn to reliable online information about menopause, from sources like the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society) and major academic health centers. Keeping a diary of changes in menstrual cycles, along with new symptoms that appear, whether they are physical or psychological, including changes in mood, can also be helpful for those discussions.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com