It was a strange Thanksgiving for Sam Altman. Normally, the CEO of OpenAI flies home to St. Louis to visit family. But this time the holiday came after an existential struggle for control of a company that some believe holds the fate of humanity in its hands. Altman was weary. He went to his Napa Valley ranch for a hike, then returned to San Francisco to spend a few hours with one of the board members who had just fired and reinstated him in the span of five frantic days. He put his computer away for a few hours to cook vegetarian pasta, play loud music, and drink wine with his fiancé Oliver Mulherin. “This was a 10-out-of-10 crazy thing to live through,” Altman tells TIME on Nov. 30. “So I’m still just reeling from that.”

We’re speaking exactly one year after OpenAI released ChatGPT, the most rapidly adopted tech product ever. The impact of the chatbot and its successor, GPT-4, was transformative—for the company and the world. “For many people,” Altman says, 2023 was “the year that they started taking AI seriously.” Born as a nonprofit research lab dedicated to building artificial intelligence for the benefit of humanity, OpenAI became an $80 billion rocket ship. Altman emerged as one of the most powerful and venerated executives in the world, the public face and leading prophet of a technological revolution.

Until the rocket ship nearly imploded. On Nov. 17, OpenAI’s nonprofit board of directors fired Altman, without warning or even much in the way of explanation. The surreal maneuvering that followed made the corporate dramas of Succession seem staid. Employees revolted. So did OpenAI’s powerful investors; one even baselessly speculated that one of the directors who defenestrated Altman was a Chinese spy. The company’s visionary chief scientist voted to oust his fellow co-founder, only to backtrack. Two interim CEOs came and went. The players postured via selfie, open letter, and heart emojis on social media. Meanwhile, the company’s employees and its board of directors faced off in “a gigantic game of chicken,” says a person familiar with the discussions. At one point, OpenAI’s whole staff threatened to quit if the board didn’t resign and reinstall Altman within a few hours, three people involved in the standoff tell TIME. Then Altman looked set to decamp to Microsoft—with potentially hundreds of colleagues in tow. It seemed as if the company that catalyzed the AI boom might collapse overnight.

In the end, Altman won back his job and the board was overhauled. “We really do feel just stronger and more unified and more focused than ever,” Altman says in the last of three interviews with TIME, after his second official day back as CEO. “But I wish there had been some other way to get there.” This was no ordinary boardroom battle, and OpenAI is no ordinary startup. The episode leaves lingering questions about both the company and its chief executive.

Altman, 38, has been Silicon Valley royalty for a decade, a superstar founder with immaculate vibes. “You don’t fire a Steve Jobs,” said former Google CEO Eric Schmidt. Yet the board had. (Jobs, as it happens, was once fired by Apple, only to return as well.) As rumors swirled over the ouster, the board said there was no dispute over the safety of OpenAI’s products, the commercialization of its technology, or the pace of its research. Altman’s “behavior and lack of transparency in his interactions with the board” had undermined its ability to supervise the company in accordance with its mandate, though it did not share examples.

Interviews with more than 20 people in Altman’s circle—including current and former OpenAI employees, multiple senior executives, and others who have worked closely with him over the years—reveal a complicated portrait. Those who know him describe Altman as affable, brilliant, uncommonly driven, and gifted at rallying investors and researchers alike around his vision of creating artificial general intelligence (AGI) for the benefit of society as a whole. But four people who have worked with Altman over the years also say he could be slippery—and at times, misleading and deceptive. Two people familiar with the board’s proceedings say that Altman is skilled at manipulating people, and that he had repeatedly received feedback that he was sometimes dishonest in order to make people feel he agreed with them when he did not. These people saw this pattern as part of a broader attempt to consolidate power. “In a lot of ways, Sam is a really nice guy; he’s not an evil genius. It would be easier to tell this story if he was a terrible person,” says one of them. “He cares about the mission, he cares about other people, he cares about humanity. But there’s also a clear pattern, if you look at his behavior, of really seeking power in an extreme way.”

Buy the Person of the Year issue here

An OpenAI spokesperson said the company could not comment on the events surrounding Altman’s firing. “We’re unable to disclose specific details until the board’s independent review is complete. We look forward to the findings of the review and continue to stand behind Sam,” the spokesperson said in a statement to TIME. “Our primary focus remains on developing and releasing useful and safe AI, and supporting the new board as they work to make improvements to our governance structure.”

Altman has spent much of the past year assuring the public that OpenAI takes seriously the responsibility of shepherding its powerful technology into the world. One piece of evidence he gave was OpenAI’s unusual hybrid structure: it is a for-profit company governed by a nonprofit board, with a mandate to prioritize the mission over financial interests. “No one person should be trusted here,” Altman told a Bloomberg Technology conference in June. “The board can fire me. I think that’s important.” But when that happened only for Altman to maneuver his way back, it seemed to underscore that this accountability was a mirage. How could a company that had brought itself to the brink of self-destruction overnight be trusted to safely usher in a technology that many believe could destroy us all?

It’s not clear if Altman will have more power or less in his second stint as CEO. The company has established itself as the field’s front runner since the launch of ChatGPT, and expects to release new, more capable models next year. But there’s no guarantee OpenAI will maintain the industry lead as billions of dollars pour into frontier AI research by a growing field of competitors. The tech industry is known for its hype cycles—bursts of engineered excitement that allow venture capital to profit from fads like virtual reality or cryptocurrency. It’s possible the breakneck pace of AI development slows and the lofty promises about AGI don’t materialize.

But one of the big reasons for the standoff at OpenAI is that everyone involved thinks a new world is not just coming, but coming fast. Two people familiar with the board’s deliberations emphasize the stakes of supervising a company that believes it is building the most important technology in history. Altman thinks AGI—a system that surpasses humans in most regards—could be reached sometime in the next four or five years. AGI could turbocharge the global economy, expand the frontiers of scientific knowledge, and dramatically improve standards of living for billions of humans—creating a future that looks wildly different from the past. In this view, broadening our access to cognitive labor—“having more access to higher-quality intelligence and better ideas,” as Altman puts it—could help solve everything from climate change to cancer.

Read More: The AI Arms Race Is Changing Everything

But it would also come with serious risks. To many, the rapid rise in AI’s capabilities over the past year is deeply alarming. Computer scientists have not solved what’s known in the industry as the “alignment problem”—the task of ensuring that AGI conforms to human values. Few agree on who should determine those values. Altman and others have warned that advanced AI could pose “existential” risks on the scale of pandemics and nuclear war. This is the context in which OpenAI’s board determined that its CEO could not be trusted. “People are really starting to play for keeps now,” says Daniel Colson, executive director of the Artificial Intelligence Policy Institute (AIPI) and the founder of an Altman-backed startup, “because there’s an expectation that the window to try to shift the trajectory of things is closing.”

On a bright morning in early November, Altman looks nervous. We’re backstage at a cavernous event space in downtown San Francisco, where Altman will soon present to some 900 attendees at OpenAI’s first developer conference. Dressed in a gray sweater and brightly colored Adidas Lego sneakers, he thanks the speech coach helping him rehearse. “This is so not my thing,” he says. “I’m much more comfortable behind a computer screen.”

That’s where Altman was to be found on Friday nights as a high school student, playing on an original Bondi Blue iMac. He grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in the suburbs of St. Louis, the eldest of four children born to a real estate broker and a dermatologist. Altman was equal parts nerdy and self-assured. He came out as gay as a teenager, giving a speech in front of his high school after some students objected to a National Coming Out Day speaker. He enrolled at Stanford to study computer science in 2003, as memories of the dot-com crash were fading. In college, Altman got into poker, which he credits for inculcating lessons about psychology and risk. By that point, he knew he wanted to become an entrepreneur. He dropped out of school after two years to work on Loopt, a location-based social network he co-founded with his then boyfriend, Nick Sivo.

Loopt became part of the first cohort of eight companies to join Y Combinator, the now vaunted startup accelerator. The company was sold in 2012 for $43 million, netting Altman $5 million. Though the return was relatively modest, Altman learned something formative: “The way to get things done is to just be really f-cking persistent,” he told Vox’s Re/code. Those who know him say Altman has an abiding sense of obligation to tackle issues big and small. “As soon as he’s aware of a problem, he really wants to solve it,” says his fiancé Mulherin, an Australian software engineer turned investor. Or as Altman puts it, “Stuff only gets better because people show up and work. No one else is coming to save the day. You’ve just got to do it.”

YC’s co-founder Paul Graham spotted a rare blend of strategic talent, ambition, and tenacity. “You could parachute him into an island full of cannibals and come back in five years and he’d be the king,” Graham wrote of Altman when he was just 23. In February 2014, Graham tapped his protégé, then 28, to replace him as president of YC. By the time Altman took the reins, YC had incubated unicorns like Airbnb, Stripe, and Dropbox. But the new boss had a bigger vision. He wanted to expand YC’s remit beyond software to “hard tech”—the startups where the technology might not even be possible, yet where successful innovation could unlock trillions of dollars and transform the world.

Soon after becoming the leader of YC, Altman visited the headquarters of the nuclear-fusion startup Helion in Redmond, Wash. CEO David Kirtley recalls Altman showing up with a stack of physics textbooks and quizzing him about the design choices behind Helion’s prototype reactor. What shone through, Kirtley recalls, was Altman’s obsession with scalability. Assuming you could solve the scientific problem, how could you build enough reactors fast enough to meet the energy needs of the U.S.? What about the world? Helion was among the first hard-tech companies to join YC. Altman also wrote a personal check for $9.5 million and has since forked over an additional $375 million to Helion—his largest personal investment. “I think that’s the responsibility of capitalism,” Altman says. “You take big swings at things that are important to get done.”

Subscribe now and get the Person of the Year issue

Altman’s pursuit of fusion hints at the staggering scope of his ambition. He’s put $180 million into Retro Biosciences, a longevity startup hoping to add 10 healthy years to the human life-span. He conceived of and helped found Worldcoin, a biometric-identification system with a crypto-currency attached, which has raised hundreds of millions of dollars. Through OpenAI, Altman has spent $10 million seeding the longest-running study into universal basic income (UBI) anywhere in the U.S., which has distributed more than $40 million to 3,000 participants, and is set to deliver its first set of findings in 2024. Altman’s interest in UBI speaks to the economic dislocation that he expects AI to bring—though he says it’s not a “sufficient solution to the problem in any way.”

The entrepreneur was so alarmed at America’s direction under Donald Trump that in 2017 he explored running for governor of California. Today Altman downplays the endeavor as “a very lightweight consideration.” But Matt Krisiloff, a senior aide to Altman at the time, says they spent six months setting up focus groups across the state to help refine a political platform. “It wasn’t just a totally flippant idea,” Krisiloff says. Altman published a 10-point policy platform, which he dubbed the United Slate, with goals that included lowering housing costs, Medicare for All, tax reform, and ambitious clean-energy targets. He ultimately passed on a career switch. “It was so clear to me that I was much better suited to work on AI,” Altman says, “and that if we were able to succeed, it would be a much more interesting and impactful thing for me to do.”

But he remains keenly interested in politics. Altman’s beliefs are shaped by the theories of late 19th century political economist Henry George, who combined a belief in the power of market incentives to deliver increasing prosperity with a disdain for those who speculate on scarce assets, like land, instead of investing their capital in human progress. Altman has advocated for a land-value tax—a classic Georgist policy—in recent meetings with world leaders, he says.

Asked on a walk through OpenAI’s headquarters whether he has a vision of the future to help make sense of his various investments and interests, Altman says simply, “Abundance. That’s it.” The pursuits of fusion and superintelligence are cornerstones of the more equitable and prosperous future he envisions: “If we get abundant intelligence and abundant energy,” he says, “that will do more to help people than anything else I can possibly think of.”

Altman began thinking seriously about AGI nearly a decade ago. At the time, “it was considered career suicide,” he says. But Altman struck up a running conversation with Elon Musk, who also felt smarter-than-human machines were not only inevitable, but also dangerous if they were built by corporations chasing profits. Both feared Google, which had bought Musk out when it acquired the top AI-research lab DeepMind in 2014, would remain the dominant player in the field. They imagined a nonprofit AI lab that could be an ethical counterweight, ensuring the technology benefited not just shareholders but also humanity as a whole.

In the summer of 2015, Altman tracked down Ilya Sutskever, a star machine-learning researcher at Google Brain. The pair had dinner at the Counter, a burger bar near Google’s headquarters. As they parted ways, Altman got into his car and thought to himself, I have got to work with that guy. He and Musk spent nights and weekends courting talent. Altman drove to Berkeley to go for a walk with graduate student John Schulman; went to dinner with Stripe’s chief technology officer Greg Brockman; took a meeting with AI research scientist Wojciech Zaremba; and held a group dinner with Musk and others at the Rosewood hotel in Menlo Park, Calif., where the idea of what a new lab might look like began to take shape. “The montage is like the beginning of a movie,” Altman says, “where you’re trying to establish this ragtag crew of slight misfits to do something crazy.”

OpenAI launched in December 2015. It had six co-founders—Altman, Musk, Sutskever, Brockman, Schulman, and Zaremba—and $1 billion in donations pledged by prominent investors like Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel, and Jessica Livingston. During OpenAI’s early years, Altman remained YC president and was involved only from a distance. OpenAI had no CEO; Brockman and Sutskever were its de facto leaders. In an office in a converted luggage factory in San Francisco’s Mission district, Sutskever’s research team threw ideas at the wall to see what stuck. “It was a very brilliant assembly of some of the best people in the field,” says Krisiloff. “At the same time, it did not necessarily feel like everyone knew what they were doing.”

In 2018, OpenAI announced its charter: a set of values that codified its approach to building AGI in the interests of humanity. There was a tension at the heart of the document, between the belief in safety and the imperative for speed. “The fundamental belief motivating OpenAI is, inevitably this technology is going to exist, so we have to win the race to create it, to control the terms of its entry into society in a way that is positive,” says a former employee. “The safety mission requires that you win. If you don’t win, it doesn’t matter that you were good.” Altman disputes the idea that OpenAI needs to outpace rival labs to deliver on its mission, but says, “I think we care about a good AGI outcome more than others.”

One key to winning was Sutskever. OpenAI’s chief scientist had an almost religious belief in the neural network, a type of AI algorithm that ingested large amounts of data and could independently detect underlying patterns. He believed these networks, though primitive at the time, could lead down a path toward AGI. “Concepts, patterns, ideas, events, they are somehow smeared through the data in a complicated way,” Sutskever told TIME in August. “So to predict what comes next, the neural network needs to somehow become aware of those concepts and how they leave a trace. And in this process, these concepts come to life.”

Read More: How We Chose the TIME100 Most Influential People in AI

To commit to Sutskever’s method and the charter’s mission, OpenAI needed vast amounts of computing power. For this it also needed cash. By 2019, OpenAI had collected only $130 million of the original $1 billion committed. Musk had walked away from the organization—and a planned donation of his own—after a failed attempt to insert himself as CEO. Altman, still running YC at the time, was trying to shore up OpenAI’s finances. He initially doubted any private investor could pump cash into the project at the volume and pace it required. He assumed the U.S. government, with its history of funding the Apollo program and the Manhattan Project, would be the best option. After a series of discussions—“you try every door,” Altman says—he was surprised to find “the chances of that happening were exactly zero.” He came to believe “the market is just going to have to do it all the way through.”

Wary of the perverse incentives that could arise if investors gained sway over the development of AGI, Altman and the leadership team debated different structures and landed on an unusual one. OpenAI would establish a “capped profit” subsidiary that could raise funds from investors, but would be governed by a nonprofit board. OpenAI’s earliest investors signed paperwork indicating they could receive returns of up to 100 times their investment, with any sums above that flowing to the nonprofit. The company’s founding ethos—a research lab unshackled from commercial considerations—had lasted less than four years.

Altman was spending an increasing amount of time thinking about OpenAI’s financial troubles and hanging out at its office, where Brockman and Sutskever had been lobbying him to come on full time. “OpenAI had never had a CEO,” he says. “I was kind of doing it 30% of the time, but not very well.” He worried the lab was at an inflection point, and without proper leadership, “it could just disintegrate.” In March 2019, the same week the company’s restructure was announced, Altman left YC and formally came on as OpenAI CEO.

Altman insists this new structure was “the least bad idea” under discussion. In some ways, the solution was an elegant one: it allowed the company to raise much-needed cash from investors while telegraphing its commitment to conscientiously developing AI. Altman embodied both goals—an extraordinarily talented fundraiser who was also a thoughtful steward of a potentially transformative technology.

It didn’t take long for Altman to raise $1 billion from Microsoft—a figure that has now ballooned to $13 billion. The restructuring of the company, and the tie-up with Microsoft, changed OpenAI’s complexion in significant ways, three former employees say. Employees began receiving equity as a standard part of their compensation packages, which some holdovers from the nonprofit era thought created incentives for employees to maximize the company’s valuation. The amount of equity that staff were given was very generous by industry standards, according to a person familiar with the compensation program. Some employees fretted OpenAI was turning into something more closely resembling a traditional tech company. “We leave billion-dollar ideas on the table constantly,” says VP of people Diane Yoon.

Buy a print of the Person of the Year covers now

Microsoft’s investment supercharged OpenAI’s ability to scale up its systems. An innovation from Google offered another breakthrough. Known as the “transformer,” it made neural networks far more efficient at spotting patterns in data. OpenAI researchers began to train the first models in their GPT (generative pre-trained transformer) series. With each iteration, the models improved dramatically. GPT-1, trained on the text of some 7,000 books, could just about string sentences together. GPT-2, trained on 8 million web pages, could just about answer questions. GPT-3, trained on hundreds of billions of words from the internet, books, and Wikipedia, could just about write poetry.

Altman recalls a breakthrough in 2019 that revealed the vast possibilities ahead. An experiment into “scaling laws” underpinning the relationship between the computing power devoted to training an AI and its resulting capabilities yielded a series of “perfect, smooth graphs,” he says—the kind of exponential curves that more closely resembled a fundamental law of the universe than experimental data. It was a cool June night, and in the twilight a collective realization dawned on the assembled group of researchers as they stood outside the OpenAI office: AGI was not just possible, but probably coming sooner than any of them previously thought. “We were all like, this is really going to happen, isn’t it?” Altman says. “It felt like one of these moments of science history. We know a new thing now, and we’re about to tell humanity about it.”

The realization contributed to a change in how OpenAI released its technology. By then, the company had already reneged on its founding principle of openness, after recognizing that open-sourcing increasingly powerful AI could be great for criminals and bad for business. When it built GPT-2 in 2019, it initially declined to release the model publicly, fearing it could have a devastating impact on public discourse. But in 2020, the company decided to slowly distribute its tools to wider and wider numbers of people. The doctrine was called “iterative deployment.” It enabled OpenAI to collect data on how AIs were used by the public, and to build better safety mechanisms in response. And it would gradually expose the public to the technology while it was still comparatively crude, giving people time to adapt to the monumental changes Altman saw coming.

On its own terms, iterative deployment worked. It handed OpenAI a decisive advantage in safety-trained models, and eventually woke up the world to the power of AI. It’s also true that it was extremely good for business. The approach bears a striking resemblance to a tried-and-tested YC strategy for startup success: building the so-called minimum viable product. Hack together a cool demo, attract a small group of users who love it, and improve based on their feedback. Put things out into the world. And eventually—if you’re lucky enough and do it right—that will attract large groups of users, light the fuse of a media hype cycle, and allow you to raise huge sums. This was part of the motivation, Brockman tells TIME. “We knew that we needed to be able to raise additional capital,” he says. “Building a product is actually a pretty clear way to do it.”

Some worried that iterative deployment would accelerate a dangerous AI arms race, and that commercial concerns were clouding OpenAI’s safety priorities. Several people close to the company thought OpenAI was drifting away from its original mission. “We had multiple board conversations about it, and huge numbers of internal conversations,” Altman says. But the decision was made. In 2021, seven staffers who disagreed quit to start a rival lab called Anthropic, led by Dario Amodei, OpenAI’s top safety researcher.

In August 2022, OpenAI finished work on GPT-4, and executives discussed releasing it along with a basic, user-friendly chat interface. Altman thought that would “be too much of a bombshell all at once.” He proposed launching the chatbot with GPT-3.5—a model that had been accessible to the public since the spring—so people could get used to it, and then releasing GPT-4 a few months later. Decisions at the company typically involve a long, deliberative period during which senior leaders come to a consensus, Altman says. Not so with the launch of what would eventually become the fastest-growing new product in tech history. “In this case,” he recalls, “I sent a Slack message saying, Yeah, let’s do this.” In a brainstorming session before Nov. 30 launch, Altman replaced its working title, Chat With GPT-3.5, with the slightly pithier ChatGPT. OpenAI’s head of sales received a Slack message letting her know the product team was silently launching a “low-key research preview,” which was unlikely to affect the sales team.

Nobody at OpenAI predicted what came next. After five days, ChatGPT crossed 1 million users. ChatGPT now has 100 million users—a threshold that took Facebook 4½ years to hit. Suddenly, OpenAI was the hottest startup in Silicon Valley. In 2022, OpenAI brought in $28 million in revenue; this year it raked in $100 million a month. The company embarked on a hiring spree, more than doubling in size. In March, it followed through on Altman’s plan to release GPT-4. The new model far surpassed ChatGPT’s capabilities—unlike its predecessor, it could describe the contents of an image, write mostly reliable code in all major programming languages, and ace standardized tests. Billions of dollars poured into competitors’ efforts to replicate OpenAI’s successes. “We definitely accelerated the race, for lack of a more nuanced phrase,” Altman says.

The CEO was suddenly a global star. He seemed unusually equipped to navigate the different factions of the AI world. “I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong, and we want to be vocal about that,” Altman told lawmakers at a U.S. Senate hearing in May. That month, Altman embarked on a world tour, including stops in Israel, India, Japan, Nigeria, South Korea, and the UAE. Altman addressed a conference in Beijing via video link. So many government officials and policy-makers clamored for an audience that “we ended up doing twice as many meetings than were scheduled for any given day,” says head of global affairs Anna Makanju. AI soared up the policy agenda: there was a White House Executive Order, a global AI Safety Summit in the U.K., and attempts to codify AI standards in the U.N., the G-7, and the African Union.

By the time Altman took the stage at OpenAI’s developer conference in November, it seemed as if nothing could bring him down. To cheers, he announced OpenAI was moving toward a future of autonomous AI “agents” with power to act in the world on a user’s behalf. During an interview with TIME two days later, he said he believed the chances of AI wiping out humanity were not only low, but had gone down in the past year. He felt the increase in awareness of the risks, and an apparent willingness among governments to coordinate, were positive developments that flowed from OpenAI’s iterative-deployment strategy. While the world debates the probabilities that AI will destroy civilization, Altman is more sanguine. (The odds are “nonzero,” he allows, but “low if we can take all the right actions.”) What keeps him up at night these days is something far more prosaic: an urban coyote that has colonized the grounds of his $27 million home in San Francisco. “This coyote moved into my house and scratches on the door outside,” he says, picking up his iPhone and, with a couple of taps, flipping the screen around to reveal a picture of the animal lounging on an outdoor sofa. “It’s very cute, but it’s very annoying at night.”

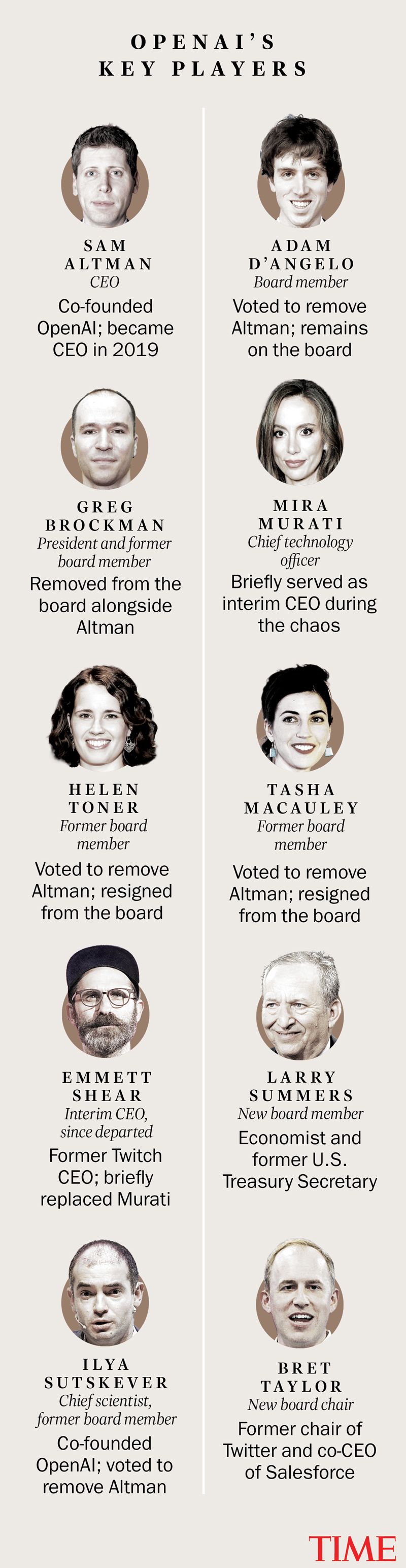

As Altman radiated confidence, unease was growing within his board of directors. The board had shrunk from nine members to six over the preceding months. That left a panel made up of three OpenAI employees—Altman, Sutskever, and Brockman—and three independent directors: Adam D’Angelo, the CEO of question-and-answer site Quora; Tasha McCauley, a technology entrepreneur and Rand Corp. scientist; and Helen Toner, an expert in AI policy at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

The panel had argued over how to replace the three departing members, according to three people familiar with the discussions. For some time—little by little, at different rates—the three independent directors and Sutskever were becoming concerned about Altman’s behavior. Altman had a tendency to play different people off one another in order to get his desired outcome, say two people familiar with the board’s discussions. Both also say Altman tried to ensure information flowed through him. “He has a way of keeping the picture somewhat fragmented,” one says, making it hard to know where others stood. To some extent, this is par for the course in business, but this person says Altman crossed certain thresholds that made it increasingly difficult for the board to oversee the company and hold him accountable.

One example came in late October, when an academic paper Toner wrote in her capacity at Georgetown was published. Altman saw it as critical of OpenAI’s safety efforts and sought to push Toner off the board. Altman told one board member that another believed Toner ought to be removed immediately, which was not true, according to two people familiar with the discussions.

This episode did not spur the board’s decision to fire Altman, those people say, but it was representative of the ways in which he tried to undermine good governance, and was one of several incidents that convinced the quartet that they could not carry out their duty of supervising OpenAI’s mission if they could not trust Altman. Once the directors reached the decision, they felt it was necessary to act fast, worried Altman would detect that something was amiss and begin marshaling support or trying to undermine their credibility. “As soon as he had an inkling that this might be remotely on the table,” another of the people familiar with the board’s discussions says, “he would bring the full force of his skills and abilities to bear.”

On the evening of Thursday, Nov. 16, Sutskever asked Altman to chat at noon the following day. At the appointed time, Altman joined Sutskever on Google Meet, where the entire board was present except Brockman. Sutskever told Altman that he was being fired and that the news would be made public shortly. “It really felt like a weird dream, much more intensely than I would have expected,” Altman tells TIME.

The board’s statement was terse: Altman “was not consistently candid in his communications with the board, hindering its ability to exercise its responsibilities,” the announcement said. “The board no longer has confidence in his ability to continue leading OpenAI.”

Altman was locked out of his computer. He began reaching out to his network of investors and mentors, telling them he planned to start a new company. (He tells TIME he received so many texts his iMessage broke.) The board expected pressure from investors and media. But they misjudged the scale of the blowback from within the company, in part because they had reason to believe the executive team would respond differently, according to two people familiar with the board’s thinking, who say the board’s move to oust Altman was informed by senior OpenAI leaders, who had approached them with a variety of concerns about Altman’s behavior and its effect on the company’s culture.

Legal and confidentiality reasons have made it difficult for the board to share specifics, the people with knowledge of the proceedings say. But the absence of examples of the “lack of candor” the board cited as the impetus for Altman’s firing contributed to rampant speculation—that the decision was driven by a personal vendetta, an ideological dispute, or perhaps sheer incompetence. The board fired Altman for “nitpicky, unfireable, not even close to fireable offenses,” says Ron Conway, the founder of SVAngel and a mentor who was one of the first people Altman called after being terminated. “It is reckless and irresponsible for a board to fire a founder over emotional reasons.”

Within hours, the company’s staff threatened to quit if the board did not resign and allow Altman to return. Under immense pressure, the board reached out to Altman the morning after his firing to discuss a potential path forward. Altman characterizes it as a request for him to come back. “I went through a range of emotions. I first was defiant,” he says. “But then, pretty quickly, there was a sense of duty and obligation, and wanting to preserve this thing I cared about so much.” The sources close to the board describe the outreach differently, casting it as an attempt to talk through ways to stabilize the company before it fell apart.

For nearly 48 hours, the negotiations dragged on. Mira Murati, OpenAI’s chief technology officer who stepped in as interim CEO, joined the rest of the company’s leadership in advocating for Altman’s return. So on the night of Sunday, Nov. 19, the board appointed a new interim CEO, Emmett Shear, the former CEO of Twitch. Microsoft boss Satya Nadella announced Altman and Brockman would be joining Microsoft to start a new advanced AI unit; Microsoft made it known that any OpenAI staff members would be welcome to join. After a tearful confrontation with Brockman’s wife, Sutskever flipped his position: “I deeply regret my participation in the board’s actions,” he posted in the early hours of Nov. 20.

By the end of that day, nearly all of OpenAI’s 770 employees had signed an open letter signaling their intention to quit if Altman was not reinstated. The same canniness that makes Altman such a talented entrepreneur also made him a formidable opponent in the standoff, able to command loyalty from huge swaths of the company and beyond.

And while mission is a powerful draw for OpenAI employees, so too is money. Nearly every full-time OpenAI employee has financial interests in OpenAI’s success, including former board members Brockman and Sutskever. (Altman, who draws a salary of $65,000, does not have equity beyond an indirect investment through his stake in YC.) A tender offer to let OpenAI employees sell shares at an $86 billion valuation to outside investors was planned for a week after Altman’s firing; employees who stood to earn millions by December feared that option would vanish. “It’s unprecedented in history to see a company go potentially to zero if everybody walks,” says one of the people familiar with the board’s discussions. “It’s unsurprising that employees banded together in the face of that particular threat.”

Unlike the staff, the three remaining board members who sought to oust Altman were employed elsewhere, had no financial stake in the company, and were not involved in its day-to-day operations. In contrast to a typical for-profit board, which makes decisions informed by quarterly earnings reports, stock prices, and concerns for shareholder value, their job was to exercise their judgment to ensure the company was acting in the best interests of humanity—a mission that is fuzzy at best, and difficult to uphold when so much money is at stake. But whether or not the board made a correct decision, their unwillingness or inability to offer examples of what they saw as Altman’s problematic behavior would ensure they lost the public relations battle in a landslide. A panel set up as a check on the CEO’s power had come to seem as though it was wielding unaccountable power of its own.

In the end, the remaining board members secured a few concessions in the agreement struck to return Altman as CEO. A new independent board would supervise an investigation into his conduct and the board’s decision to fire him. Altman and Brockman would not regain their seats, and D’Angelo would remain on the panel, rather than all independent members resigning. Still, it was a triumph for OpenAI’s leadership. “The best interests of the company and the mission always come first. It is clear that there were real misunderstandings between me and members of the board,” Altman posted on X. “I welcome the board’s independent review of all recent events.”

Two nights before Thanksgiving, staff gathered at the headquarters, popping champagne. Brockman posted a selfie with dozens of employees, with the caption: “we are so back.”

Ten days after the agreement was reached for their return, OpenAI’s leaders were resolute. “I think everyone feels like we have a second chance here to really achieve the mission. Everyone is aligned,” Brockman says. But the company is in for an overhaul. Sutskever’s future at the company is murky. The new board—former Twitter board chair Bret Taylor, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, and D’Angelo—will expand back to nine members and take a hard look at the company’s governance. “Clearly the current thing was not good,” Altman says.

OpenAI had tried a structure that would provide independent oversight, only to see it fall short. “One thing that has very clearly come out of this is we haven’t done a good job of solving for AI governance,” says Divya Siddarth, the co-founder of the Collective Intelligence Project, a nonprofit that works on that issue. “It has put into sharp relief that very few people are making extremely consequential decisions in a completely opaque way, which feels fine, until it blows up.”

Back in the CEO’s chair, Altman says his priorities are stabilizing the company and its relationships with external partners after the debacle; doubling down on certain research areas after the massive expansion of the past year; and supporting the new board to come up with better governance. What that looks like remains vague. “If an oracle said, Here is the way to set up the structure that is best for humanity, that’d be great,” Altman says.

Whatever role he plays going forward will receive more scrutiny. “I think these events have turned him into a political actor in the mass public’s eye in a way that he wasn’t before,” says Colson, the executive director of AIPI, who believes the episode has highlighted the danger of having risk-tolerant technologists making choices that affect all of us. “Unfortunately, that’s the dynamic that the market has set up for.”

But for now, Altman looks set to remain a leading architect of a potentially world-changing technology. “Building superintelligence is going to be a society-wide project,” he says. “We would like to be one of the shapers, but it’s not going to be something that one company just does. It will be far bigger than any one company. And I think we’re in a position where we’re gonna get to provide that input no matter what at this point. Unless we really screw up badly.” —With reporting by Will Henshall/Washington and Julia Zorthian/New York

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Naina Bajekal/San Francisco at naina.bajekal@time.com and Billy Perrigo/San Francisco at billy.perrigo@time.com